A guest post by historian Sara A. Porterfield, Ph.D. Candidate, University of Colorado at Boulder

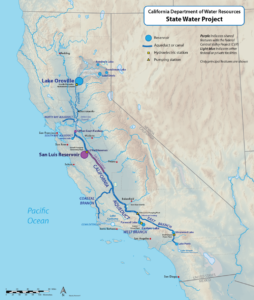

Modern USBR map

As I was working on a draft of my dissertation’s introduction a couple months ago, I decided that I HAD to know what percentage of the Colorado River Basin lies in Mexico. This factoid would have taken up half of a sentence and wasn’t necessary to my argument or larger purpose, but I was probably subconsciously (ok, consciously) looking for a way to procrastinate tackling the larger issues of the introduction, like formulating my argument. I put this question out to the #CORiver Twitterverse, and John, Abby Burk (of the Audubon Society), and I started an email chain that went way, way down a Colorado River rabbit hole.

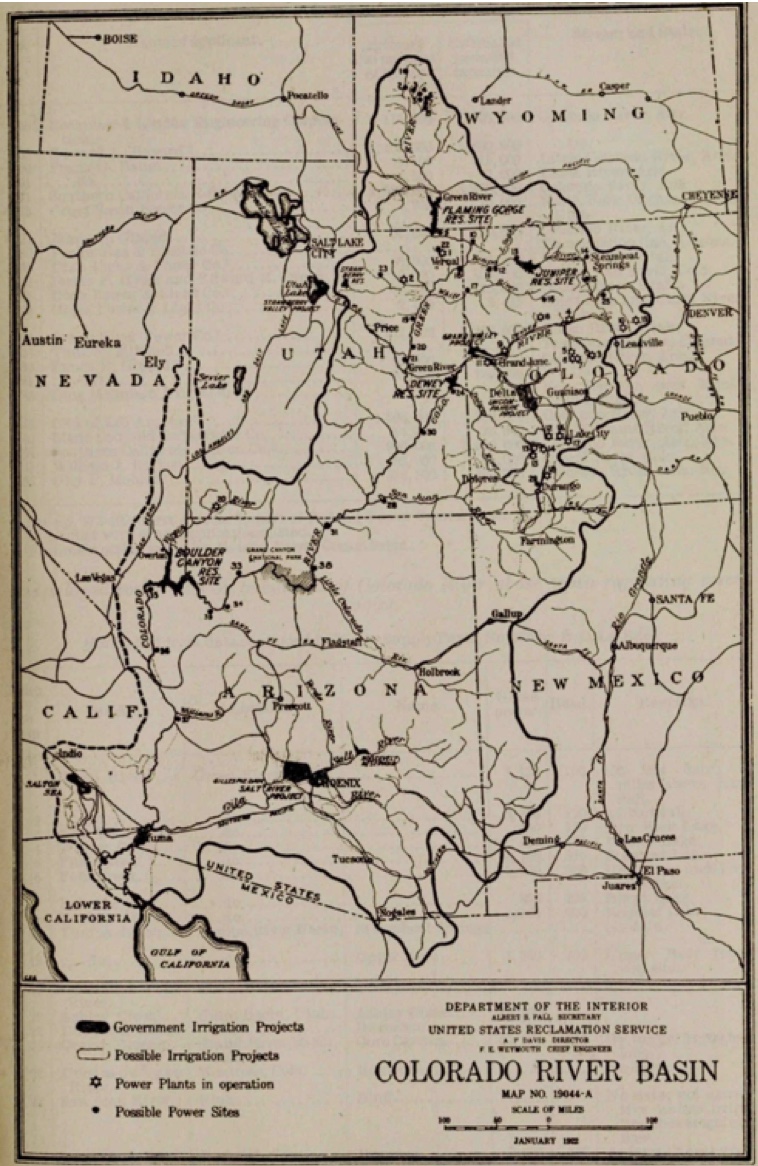

Somewhere in that email chain John sent along a 1928 map of the Colorado Basin that included Mexico, writing that he was “fascinated by what they were thinking about in 1928 that made them include it. It certainly was not a time during which we were cheerfully thinking about sharing water with Mexico.” I looked at the map and thought what was Mexico doing on that map? This sounded like a job for a historian!

1928 USBR map

I spent a little time looking at both the newer U.S. Bureau of Reclamation map that includes Mexico and the 1928 map John had sent me. Here’s my theory about why the Bureau would have included Mexico in their 1928 map.

I spent a little time looking at both the newer U.S. Bureau of Reclamation map that includes Mexico and the 1928 map John had sent me. Here’s my theory about why the Bureau would have included Mexico in their 1928 map.

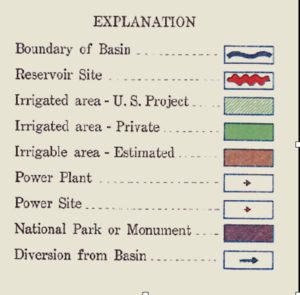

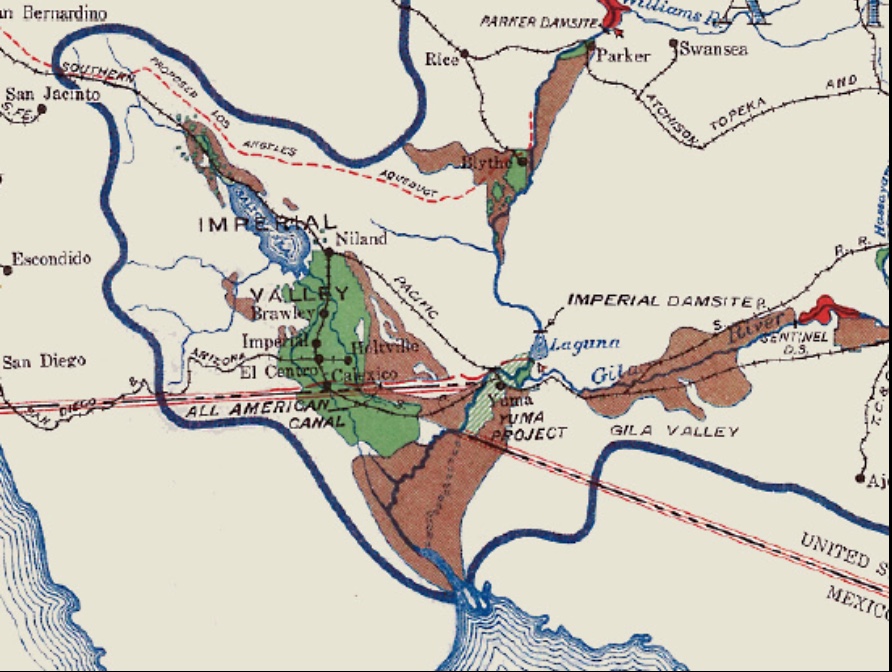

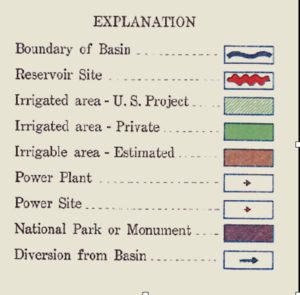

The key to the 1928 map is what really got me thinking. There’s reservoir sites, national parks/monuments, and power projects listed, sure, but the only thing in the key that appears in the Mexican part of the Basin is the dark green of the private irrigated areas and the dark brown of the estimated irrigable areas.

This made me think that those making (or directing the making of) the 1928 map were far more concerned with irrigation potential than with geographic/hydrologic accuracy, as the modern map seems to take as its aim. The irrigation and potential irrigation marked on the 1928 map led me to that conclusion, as well as the fact that they extended the Basin to include the Salton Sink/Imperial Valley—which it doesn’t today.

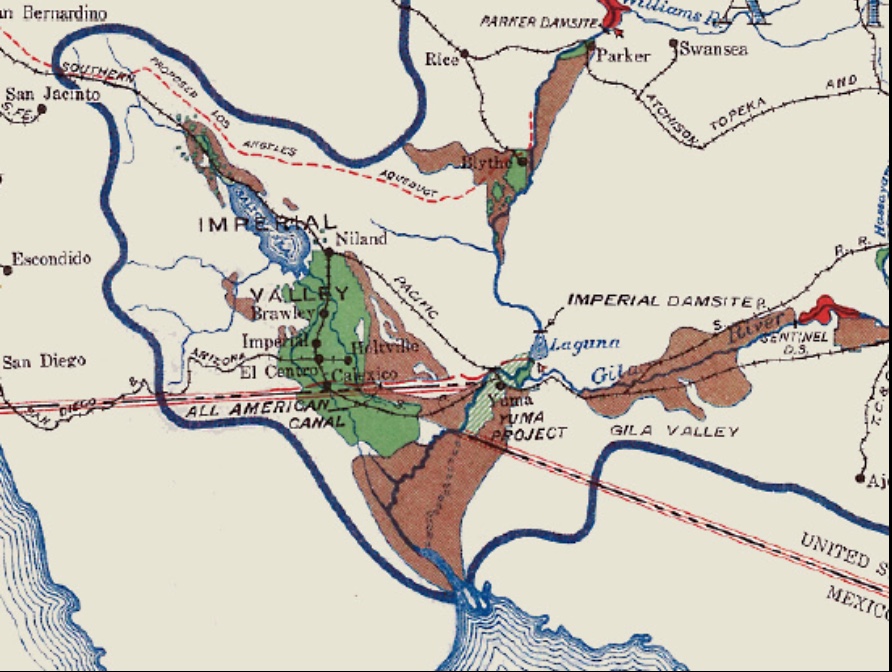

Lower Colorado, from 1928 USBR map

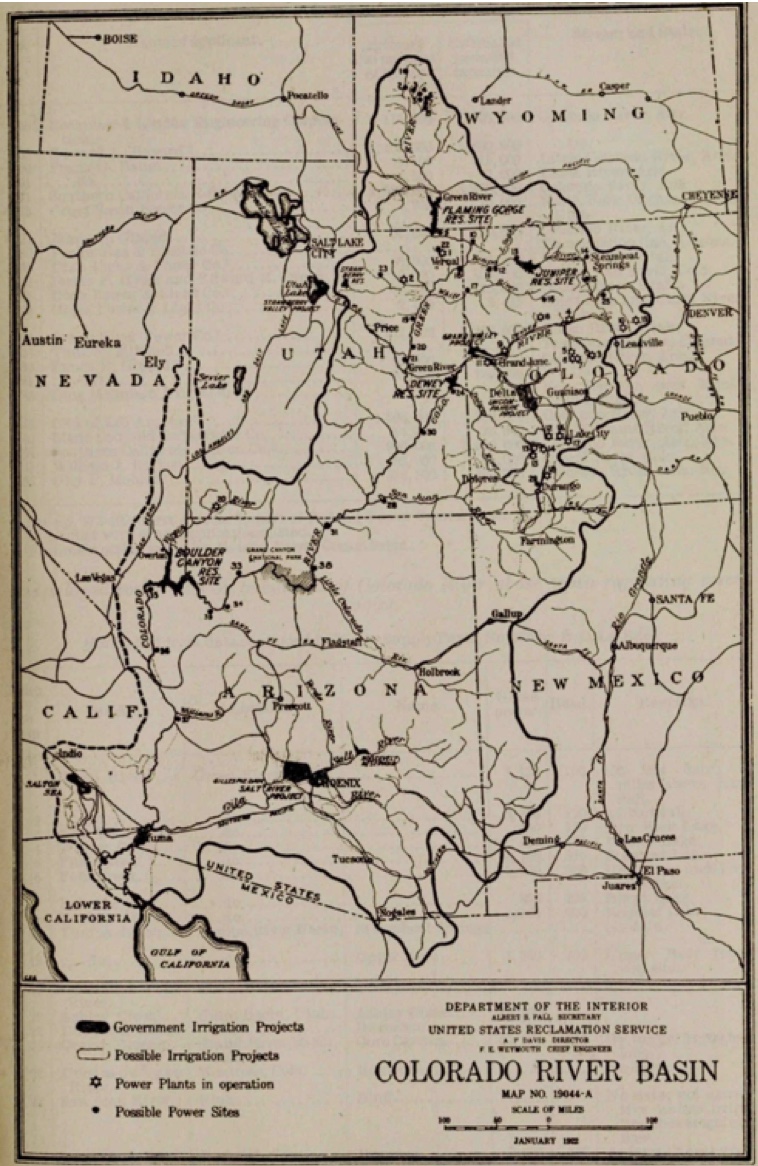

So, after looking through my research database and not finding anything, I remembered the Fall-Davis Report, officially titled Problems of Imperial Valley and Vicinity and published in 1922.

Bingo.

The Basin map included in the Fall-Davis Report is almost identical in outline to the 1928 map from John. The Fall-Davis map is quite a bit simpler than the 1928 map and doesn’t seem to have the key/shading the 1928 map does—just a Basin outline with existing and potential irrigation and hydropower projects.

Fall-Davis Report map

The Fall-Davis Report advocated for the construction of two projects: Hoover Dam and an “All-American” Canal, and I think these two projects help us understand why the 1928 map and the Fall-Davis map were drawn the way they were. First, Imperial Valley irrigators and BuRec engineers wanted Hoover Dam (then called Boulder Dam) for flood control to protect irrigation in the delta region. The floods of 1905-1907 that tore out an Imperial Valley headgate and created the Salton Sea were a not too distant memory for Imperial Valley residents and Bureau engineers—and Davis and others in BuRec wanted to do everything in their power to prevent that from happening again. From this, I can see why they would have drawn the Basin to include the Salton Sink since the river could, conceivably, change course and flood the Imperial Valley again at any moment, thus destroying the booming agricultural industry there. Drawing the Salton Sink into the map made clear the threat of the river doing this again.

Second—and more to the point—I believe these maps include Mexico because the U.S. was worried about Mexico taking water out of the Alamo Canal on its way to the Imperial Valley. The geography of the eastern side of the Imperial Valley along the western bank of the Colorado was such that it was difficult to construct a canal due to a sea of sand dunes with a tendency to drift, so the original Imperial irrigators negotiated with Mexico to bring water to the Imperial Valley via the Alamo Cana. The Alamo took water out of the Colorado in Mexico, diverted it south of those pesky sand dunes, and then delivered the water to Imperial irrigators across the California line. Those irrigators worried that Mexican irrigators would try and steal “their” water on its way to their crops—and therefore advocated for an “All-American” Canal that would eliminate the need to bring water through Mexico (For more on this, see “Chapter 2: Imperial Joins the Crusade” in Norris Hundley’s Water and the West).

So.

The 1928 map as well as the Fall-Davis map (to a lesser extent) included Mexico and its irrigated and potentially irrigated acreage in order to make the argument for the All-American Canal. Those making the maps—including BuRec bureaucrats and engineers and Imperial irrigators—wanted to scare legislators into thinking that Mexico could develop tens of thousands of acres of land with water “stolen” from the Alamo Canal. The Fall-Davis Report says as much: “The Imperial irrigation district contains more than 100,000 acres of irrigable land not yet irrigated and the same valley in Mexico can increase over 40,000 acres, and is in a physical position to take the necessary water from the Imperial [Alamo] Canal before it reaches the California line” (p. 6).

The BuRec didn’t include Mexico in its 1928 map out of the goodness of their heart or out of an allegiance to hydrologic accuracy, but because they wanted to shut down agriculture in the Mexican delta. What can seem like a cartographic anomaly—the inclusion of a portion of the Basin not seen until the twenty-first century popping up in an early-twentieth-century map—reveals the map makers’ motives, how the U.S. valued water, and the status of the nation’s diplomatic relationship with Mexico in that moment. These hidden histories uncover the Colorado’s past and help us understand more clearly the current dynamics at play in the Colorado Basin today.

– Sara Porterfield

I spent a little time looking at both the newer U.S. Bureau of Reclamation map that includes Mexico and the 1928 map John had sent me. Here’s my theory about why the Bureau would have included Mexico in their 1928 map.

I spent a little time looking at both the newer U.S. Bureau of Reclamation map that includes Mexico and the 1928 map John had sent me. Here’s my theory about why the Bureau would have included Mexico in their 1928 map.