We’re going to need a bigger graph.

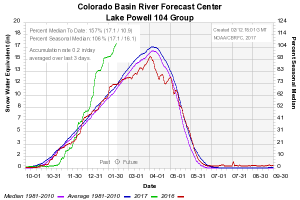

While we were all distracted by the chaos at Oroville Dam, the snowpack above Lake Powell on the Colorado River last week climbed above normal for the year. By this measure from the CBRFC, it’s at 57 percent above average for mid-February. It doesn’t usually peak until early April.

Based on the latest round of forecasts, expect it to keep rising. This is good news for levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two large reservoirs that provide storage for basin water users.

The current model estimate for April – July flow into Lake Powell is a staggering 3.5 million acre feet above the Jan. 1 forecast. To get a sense of the scale of that, Lake Powell currently holds 11.2 million acre feet of water. 3.5 maf is a meaningful increase in storage. The Bureau of Reclamation’s monthly operations report, out today, projects Powell ending September with a surface elevation of 3,640 feet above sea level, 32 feet above the forecast just a month ago.

But beyond gobs of water, what does it mean? First and most importantly, it puts off the risk that Lake Powell could drop to a level that puts at risk the ability of the Upper Colorado River Basin to meet its delivery obligations under the Colorado River Compact. The bureau also has concluded it is likely there will be enough water in the system to release “bonus” water from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin, helping prop up Lake Mead with a release of 9 million acre feet this year, above the minimum required release of 8.23 maf. (Though as astute Inkstain reader Charles notes, the rules are complicated and we’ll have to wait until April to know for sure about this.)