Upcoming discussions in my spring University of New Mexico Water Resources Program class about the importance of evidence in policy-making seem freshly relevant.

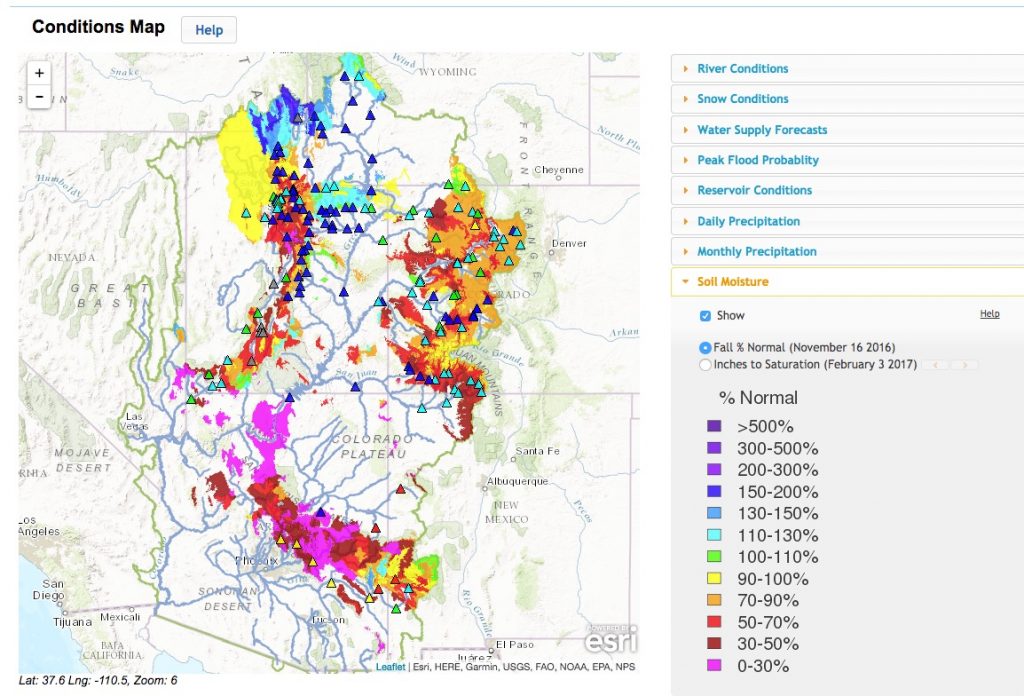

The class, co-taught with hydrologist Jesse Roach and economist Jingjing Wang, has a pretty nerdy focus on dynamic simulation modeling. Over the course of the semester, the students work through the problem of building a model (we use Powersim) of a river basin. They build in both the physical part – hydrology, climate, etc. – and the human part with Jingjing’s economics component. Alongside all of that, I help the students work through the question of how their technical work interfaces with the political and policy world – how to make their technical work relevant.

A big part of my piece is communication – how to write up what they’re finding for a non-technical audience, the hypothetical mayor or county commissioner who does not have the technical background of the college professor the students are used to writing for.

A big part of that task is understanding way evidence is received in political and policy processes.

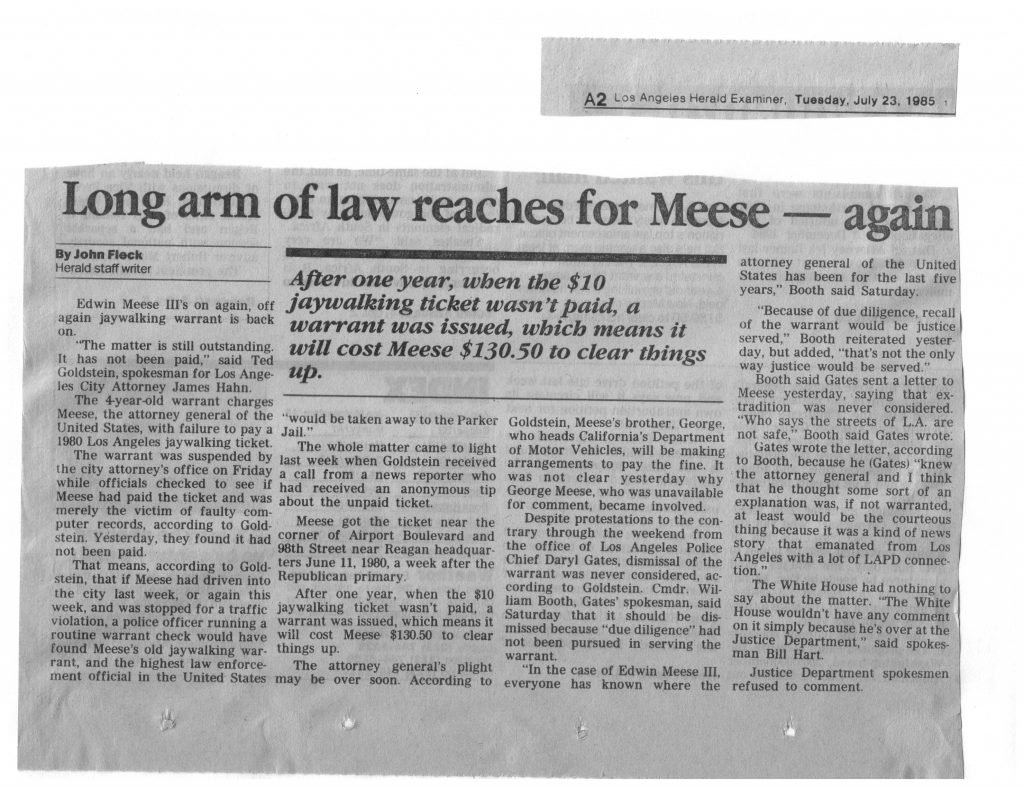

In the sciency academic world, there’s a strong and understandable inclination to argue for the supremacy of technical evidence in decision-making. As a result, academics tend to get frustrated with the way things actually work. We are seeing that play out over the past week, as our new president pursues policies that seem to fly in the face of the evidence with respect to the impacts and risks associated with immigrants to the United States.

My core messages is that simply saying, “But evidence!” ever louder, as often is done in these cases, does not work.

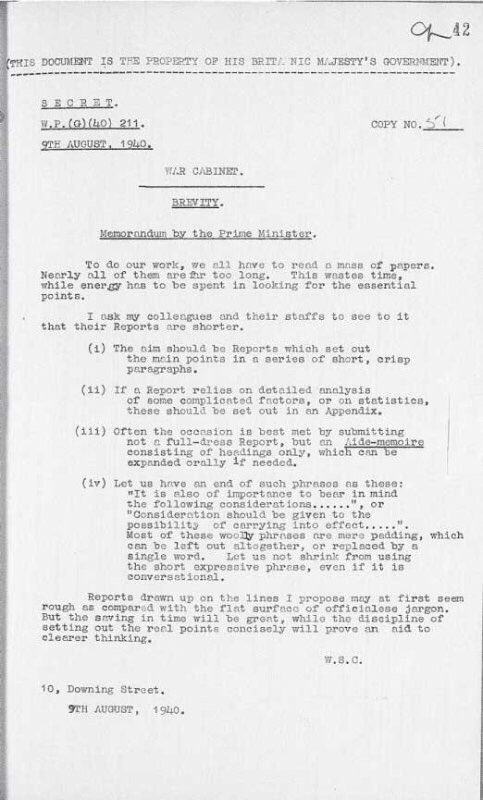

Paul Cairney, Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the University of Stirling in the UK, had a timely post last week in this regard:

Too much ‘post-truth politics’ discussion is self-indulgent. Too many academics are quick to demonise the cynical world of politics and politicians and to romanticise their own causes or objectivity. They need to acknowledge that ideological and emotional thinking is a natural part of life, and a part of life to which they are not immune. ‘Experts’ are storytellers for their own cause, and they tell each other the same story about post-truth politics. What separates them from their competitors is that the latter are better at telling effective stories which manipulate the beliefs and emotions of their audience.

So, what can they do about it? Tell good, positive stories, combining scientific evidence with emotional hooks, to help people understand and care about important political issues.

You can see this in the response to our new president’s executive order regarding refugees and immigration. The evidence crowd offers a strong case that the people impacted by the order pose little risk. But the communication tool that proved successful in this first skirmish of a long battle over this policy was the human stories of the innocent people impacted by the measure.

Some timely lessons playing out here in real time, I recommend reading Cairney’s piece in full.