I’m talking with University of New Mexico Water Resources Program students about the Colorado River this week, and pulling together some readings I had occasion to revisit the opening of The New Book:

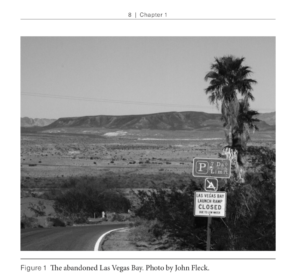

The boat ramp at Las Vegas Bay, once a shimmering recreation mecca on the shores of Lake Mead, now ends in a row of concrete barricades and desert sand. A short hike through the scrub leads to an incongruous flowing river, the effluent from the Las Vegas metro area’s wastewater treatment plants, flowing the last few miles to Lake Mead.

The floating marina that once anchored Las Vegas Bay here was moved in 2002, towed to deeper water as Lake Mead declined. The great reservoirs integrate the Colorado River’s two stories—nature’s water flowing in, and humans taking it out. Too little of the first, or too much of the second, is in the long run unsustainable. At the bottom of the old Las Vegas Bay boat ramp, you can look up and see which version of the story is playing out etched in the hillsides above, old shorelines long since left dry by Lake Mead’s decline.

It was one of the very last bits of the book we wrote, in mid-December 2018. My co-author Eric Kuhn and I had been holed up for much of the week in a suite at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, slipping away from the Colorado River Water Users Association downstairs to squeeze in time banging away at the manuscript.

The CRWUA meeting is the most important annual gathering of the Colorado River community, and it was there three years earlier, at one of the free-drinks-and-hors d’oeuvres events that are a CRWUA necessary evil, that a conversation between Eric and I launched what would become the book. So it was a fitting place to launch the final push.

The manuscript had been sorta done for months, but then all of a sudden the book contract->final revisions process had exploded on us in a hurry, with less than a month to respond to reviewers’ comments and polish off the final version. It was a crazy, nervous time.

And I still wasn’t satisfied with the book’s opening.

In our division of labor, Eric was the Colorado River genius (y’all who know him already know that), while I tried to bring a storytelling structure and literary voice to help usher that genius into our readers’ worlds.

We took the book’s opening seriously, had been reworking it since early in the project, trying and discarding a bunch of stuff.

Leaving Las Vegas with the final draft of the opening still hanging, I drove out through Henderson, around Lakeshore Road along the western edge of Lake Mead on my way to Boulder City. When I can I drive to Las Vegas from Albuquerque rather than fly, and often leave some time on one end of the trip or the other to visit Lake Mead and Hoover Dam. This trip, I had a room the night after CRWUA at the old Boulder Dam Hotel, with time to wander.

I’ve been visiting those same places along the western edge of Lake Mead since 2010, grasping for the physical representation of the thing I’ve devoted the last decade to writing about – “The great reservoirs integrate the Colorado River’s two stories—nature’s water flowing in, and humans taking it out.”

Writing a thing like this is impossible to force, which made this a particularly unnerving moment – a deadline weeks away on one of the most important projects of my life. The trick is to place yourself in a moment and hope that the bucket of intellectual building blocks you’ve got in reserve will fall into the right places around it.

I parked the car at the end of the old Las Vegas Bay boat ramp and walked toward the water.

I can see the mental progression in the cell phone pictures I snapped that day – looking down at the water flowing down Las Vegas Wash, then out at the distant reservoir, then back up at the hillside behind me.

At some point that afternoon I picked up a dead reservoir clam and snapped a picture (Corbicula fluminea or Asian clam, Karl Flessa later told me), then looked again, back up at the hillside. I drove south, stopped again at Boulder Harbor and did the same thing. Once I realized what I had, what I needed to do, I was kicking myself for not bringing the good camera.

To be clear, I’d been standing at the reservoir’s edge looking back up at “the story … playing out etched in the hillsides above” for a while. It’s a fascinating institutional geomorphology, traces on the landscape left by human water management decisions. But it didn’t find its place among my bucket of intellectual building blocks until that afternoon.

Pingback: The problems of a rising Lake Mead – jfleck at inkstain