I’m not sure who came up with the “More Slices than Pie” title for the panel discussion I moderated Thursday at the annual meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association, but it had a nice ring. A big thanks to Tom McCann from the Central Arizona Project for putting the panel together and inviting me to help out. Important audience, important messages about the risks if basin water managers can’t come to grips with the need to stop draining their reservoirs so quickly.

There’s some important signaling here. For a long time, this thing we have come to call the “structural deficit” – the reality that paper allocations on the river exceed actual water supply – was an elephant in the room. It’s not that the overallocation problem was ignored in official discussions. People both inside and outside the basin’s water management institutions have talked about this for years.

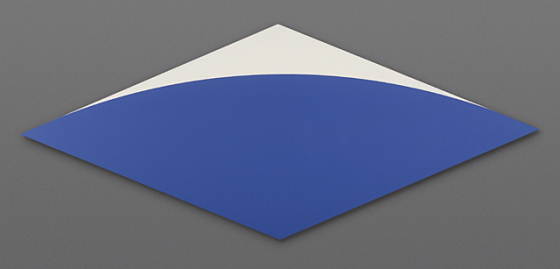

Doug Kenney, University of Colorado, December 2010

This image, for example, is from a 2010 presentation at CRWUA by the University of Colorado’s Doug Kenney pointing out that under normal water supply conditions (never mind drought or climate change) there is not enough water to keep Lake Mead from shrinking. In October of 2010, Lake Mead had dropped to historic lows, but then it got wet (Mead rose 46 feet in 2011) and the pressure was off.

There is a tension in the Colorado River management between the core group of managers operating at the basin scale who are trying to work out ways to deal with the overall shortfall, and water managers working at more local scales back home, who just want the water promised to them on paper by the deals negotiated back in the day. When it gets wet, as it did in the winter of 2010-11, it takes the pressure off of that conflict, because we can simply keep using water and sucking down the reservoirs rather than dealing with the shortfall.

But Mead is back to its record-setting lowest-it’s-been-since-it-filled ways. Thursday’s session putting the basin’s overallocation problem on the main stage at CRWUA for discussion by representatives of four of the major Colorado River Basin water agencies suggests that managing scarcity and risk rather than assuming abundance is, at least for now, the conventional narrative.

Caeser’s Palace, the annual meeting place of the Colorado River Water Users Association

CRWUA is a strange and wonderful thing, an annual gathering that brings all the disparate elements of the disaggregated Colorado River water management community – federal, state, local, farm, city, environmental, recreation – together in one spot. In a system in which no one is in charge, this ritualized annual coming together is critical for the social capital needed to deal with the basin’s tough issues. I wish I had the formal skills of an anthropologist or one of those people who studies formal and informal networks. CRWUA would make a great field study area.

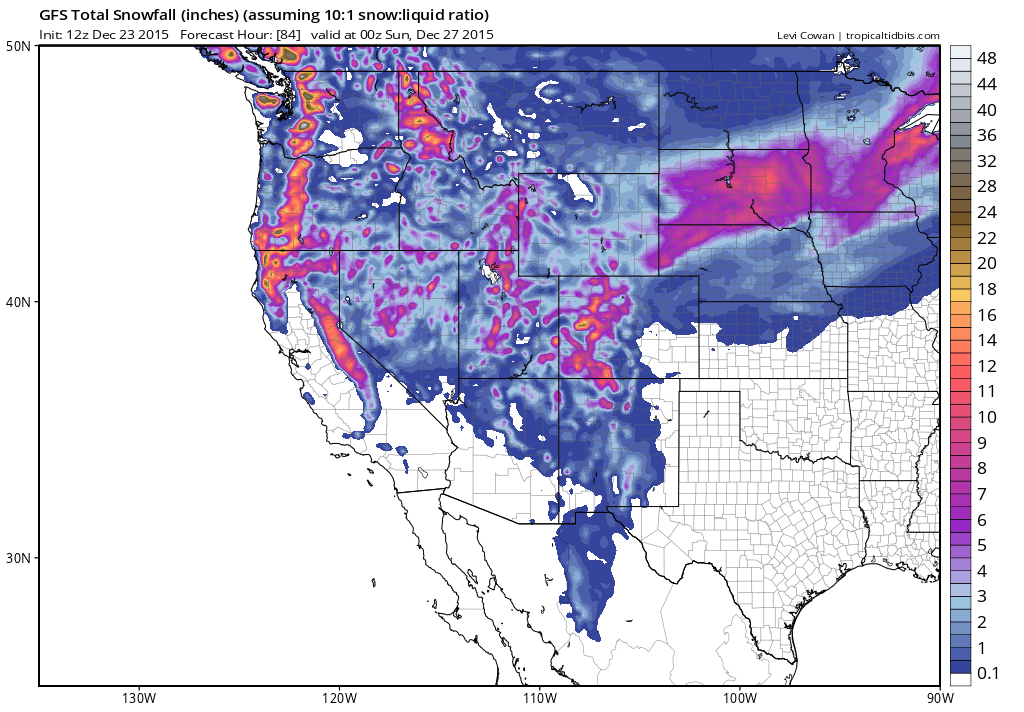

There’s an odd turn of phrase that I’m increasingly hearing in the Colorado River management community in describing the risk of Lake Mead dropping in a hurry – “blowing through 1,020”. It’s an action verb, describing a reservoir in free fall if we don’t get bailed out by whatever the opposite of climate change and drought are. The problem is that as reservoir levels decline, the V-shaped profile of the big Colorado River reservoir means that there’s less water for a given amount of elevation, which means that we shift quickly from dropping five or ten or fifteen feet per year to plummeting from 1,020 to 895 in a hurry. When I started working on Colorado River issues, “895”, the level at which you can’t get water out of Lake Mead, didn’t get talked about much. But the number came up a lot at this year’s CRWUA.

Deputy Secretary of the Interior Mike Connor, in a talk yesterday, said the latest Bureau of Reclamation analyses put the risk of 1,020 in the next five years at somewhere between 11 and 30 percent. At those kinds of low reservoir levels, managing the system becomes far more difficult, and cuts needed to prevent the doomsday scenario are far more extreme.

The trick is for the basin leaders who understand this to craft a deal with the wisdom to make some water use reductions before 1,020 (or 1,030, or 1,040, or whatever) in a way that trades benefits of using that water now for a reduction in future risk.

The immediate problem now is in the Lower Basin, the states of Nevada, California, Arizona, Sonora, and Baja. The Upper Basin has its issues, involving how much water will be available to support future growth, but in the Lower Basin the question is how much water is available to support the farms and cities we’ve already got.

Lake Mead from the air, flying into Las Vegas

It’s pretty clear what a Lower Basin deal has to look like in general terms. It’s all about Arizona and California, which are by far the biggest users. Unless each state is willing to reduce its take on Lake Mead, it would be easy to blow through 1,020 in a hurry, as Connor’s numbers suggest. I’m confident (this is a lot of what my book is about) that both states have the capacity to continue to thrive on substantially less less water, both agriculture and cities, if we do it right. My forthcoming book spends a lot of time on what this adaptive capacity already looks like. But if Arizona and California don’t move soon and we blow through 1,020 with the resulting need for cuts that are deep and fast, my confidence about the grace with which we can adapt goes down.

Talks have been underway on this for a while, under the label “drought contingency planning”. (I hate that word – it’s not a drought! This is what normal looks like!) Connor and others suggested at CRWUA that agreement is near. There will be nuances to the deal, in terms of who takes how much reduction at what reservoir levels. The idea, as one of the senior federal officials explained, is a series of voluntary agreements (“At reservoir level X, we agree to take this much less water”) developed within the framework of the basin’s 2007 shortage sharing rules, but with larger reductions to slow the reservoir’s fall. The trick now will be for the negotiators to head back home and convince local water users that those paper water entitlements written into laws over the last hundred years are not real, and that for the health of the system they’ll have to adapt to the reality that there’s less water to go around.

This is the phase of the process I worry about most. There are tensions betweens states, and also among water users within states. Bad water politics back home (“Why are we giving up water just so Arizona/California/Phoenix/LA/Imperial/Yuma can have it!”) could scupper a deal. At that point, we could blow through 1,020 in a hurry.

CRWUA is a good place for that conversation to happen, because it’s a mix of both kinds of water managers – those who work at the basin scale, and those who have to deliver the water to farm gates and shower heads back home.