Matt Weiser, who has ably served so many of us as a guide to the complexities of California water, is leaving the Sacramento Bee.

Exaggerated Impacts of Unrealistic Water Shortages

A guest post of sorts* from a group of prominent economists here in the western United States questioning the findings in a widely quoted report (pdf here) by a group from Arizona State about the potential economic impact if the Colorado River went dry:

***********

A January 14th article in the Wall Street Journal reported results of a study that estimated economic losses to the seven Colorado River Basin States should the Colorado River dry, and, with it, a loss of critical water supply to the regional economies. The study tallies the annual contribution of the Colorado to the combined Gross State Product of the Basin at about one twelfth of the total U.S. GDP. The regional losses cited in the study range from $43,000 to $394,000 per acre-foot, our usual measure of water quantity. Anyone familiar with market water values in the region that typically range from $100 to $300 per acre foot will be skeptical of the loss estimates.

Values in California during its current drought have reached $2000 per acre foot. It is unrealistic to assume that the Colorado will dry up, although it is well known that recent flows have been falling and that storage in the Basin’s reservoirs is at an historic low. Further, ways of mitigating such huge losses are ignored in the study: (1) increased water use efficiency by urban and (especially) agricultural users; (2) use of groundwater in the short term; (3) desalination of plentiful brackish waters priced around $1000 per acre-foot; (4) imports from other regions. The study’s approach ignores these possibilities and assumes that historical ratios of water use to output must continue unchanged. It ignores the contribution of other inputs such as power, land, and capital.

Study statements that 65.8% of New Mexico’s annual state output would be lost are, prima facie, not credible since only 15% of New Mexico’s irrigation water comes from the Colorado and only 60% for urban uses according to the study.

Good policy needs to be based on sound economic analysis. Distorted analyses serve no interests well.

Frank Ward, Professor of Agricultural Economics, New Mexico State University; R. Garth Taylor, Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics, University of Idaho; Charles W. Howe, Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Colorado; George Frisvold; Professor of Agricultural Economics, University of Arizona

* Originally written as a letter to the editor to the Wall Street Journal, not published there, published here by permission of the authors

As the water drops, so does the power.

As I empty the last of last month’s big snowstorm from my rain barrels onto the garden, I notice the water comes out more and more slowly. It’s a reminder of why power production drops as supply in our big reservoirs declines. Some tricky tradeoffs here:

How Southern California quietly doubled its 2014 supply of Colorado River water

Resilience is a system’s ability to absorb a shock and still retain its basic structure and function.

Here, in one complicated table, is an example of the sort of institutional plumbing valves we need to build to increase resilience in the face of drought. It’s a table accounting for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s diversions of Colorado River Water in 2014, water that provided a buffer against California’s extraordinary drought, and it shows how Met essentially doubled the amount of water it was able to take from the Colorado River in 2014 to meet the needs of coastal cities:

The key point to understand is that under the basic Colorado River water allocation rules, Met is entitled to 550,000 acre feet of water per year in a “normal”, non-surplus year, but last year it took more than twice that: 1.18 million acre feet. It did that by invoking a long list of policy widgets that allowed it to either pay for conservation in other places, or to conserve water in previous years that was banked in Lake Mead for later use.

- 113,400 acre feet of water saved by lining canals in the Imperial and Coachella, the region’s two big ag water districts

- 100,000 af saved by fallowing land in Imperial

- 67,700 af saved by lining the All-American Canal

- 338,500 af that had been saved through conservation efforts and banked in Lake Mead

Each one of these widgets is the result of the unglamorous work of building personal and institutional relationships among water users and agencies, many of them across the difficult ag-urban interface. They were built over time, and are now available when they’re needed. They have added resilience to the system.

Rhees to head USBR Upper Colorado office

The Bureau of Reclamation today named Brent Rhees to head its Salt Lake City-based Upper Colorado office:

As deputy regional director, Rhees managed several complex and high profile issues, including the Middle Rio Grande Endangered Species Collaborative Program, dam safety modifications, implementation of the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project, the Colorado River Salinity Control Program and completion of the Animas La-Plata Project.

The Colorado – as human construct, and face to flow

Water journalist Brett Walton wrote a lovely piece about finally meeting the Colorado River for the first time:

I have reported on the Colorado River for five years. I know it as a legal argument, as a topographic feature, as an obstacle, and as a matrix of charts, calculations, and grim projections. I’ve read its case law. I’ve driven across its two monumental dams, and I’ve admired its curves through an airplane window. Its history — legal, political, environmental — is as vivid to me as any river’s. Yet, until this week, I had never touched its waters.

Feet swollen from the 4,460-foot descent and body breathless but euphoric, I removed my shoes and walked across the soft sand of Pipe Creek beach. The water appeared emerald or olivine depending on the angle of the sun. I bent low, bringing my lips to the river and took a drink.

The Colorado River’s Parker valley – “the illusion of plenty”

Parker Live, a news web site based in Parker, Arizona, seems to be engaging in a little bit of what Kathryn Sorensen calls “drought schadenfreude” here. Parker sits on the Colorado, at the head of a rich farming valley with some of the most senior rights on the river and big farming that has thus far been unfazed by drought. But there is a nervous tone to the thing, as if everybody’s looking over their shoulder:

It’s easy to forget that there’s a drought when Lake Havasu and Lake Moovalya are full of beautiful, crystal clear water and the bigger cities around us are lush with green lawns and landscaping. But that may begin to change soon….

The Parker valley, a rich agricultural area made possible by irrigation, is theoretically safe because it is part of the Colorado River Indian Tribes reservation and utilizes water rights owned by CRIT. But CRIT officials, speaking at the recent 150th year commemoration of the establishment of the reservation, are warning that their water rights will be under attack in the coming months and years. With water becoming a more precious resource, municipalities will be turning their attention anywhere they can get it. “The fight over our water lies ahead of us,” said CRIT Council Chairman Dennis Patch.

If you look at the picture, you’ll see that the desert here is never very far away.

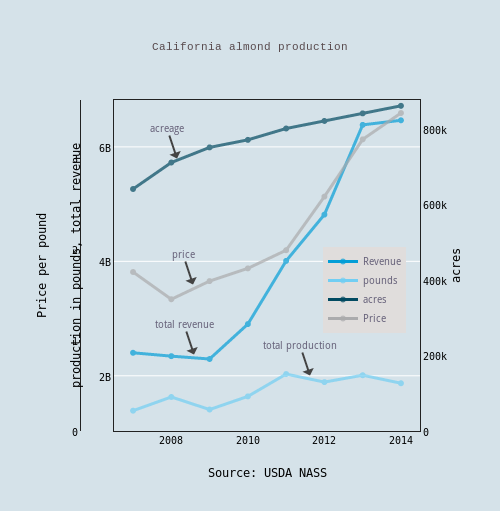

California almonds

The price California farmers can get for their almonds doubled between 2007 and last year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Strong incentive to plant more trees, drought notwithstanding:

Dams, water, and the Arizona state seal

Arizona’s state seal is a fascinating bit of iconography in light of the state’s uneasy relationship with aridity and developed water. A dam, a river and irrigated land are given center stage – water projects as state destiny. Today I learned the seal’s details are actually enshrined in the state constitution:

In the background shall be a range of mountains, with the sun rising behind the peaks thereof, and at the right side of the range of mountains there shall be a storage reservoir and a dam, below which in the middle distance are irrigated fields and orchards reaching into the foreground, at the right of which are cattle grazing.

The clouds, apparently, are optional.

Roosevelt Dam was not yet completed when the above language was written during the 1910 constitutional convention, but those gathered were all about the future.

In drought, would peripheral tunnels doom the Sacramento delta?

Doug Obegi lays out an interesting argument about the implications of drought for the “Bay Delta Conservation Plan”, the California plan to build great water-carrying tunnels beneath the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta for farms and cities to the south.

On paper, the tunnels would be largely dry during drought years, to preserve salinity balance in the delta, including for those who get their water there. But the tunnels would make it physically possible, Obegi argues, to just suck up the entire Sacramento River in a dry year like this, if Californians were willing to write off the delta, removing the fresh water flow that keeps sea water at bay. It thus becomes a political question, and there is some precedent for the politics of water allowing the saltwater to intrude, he argues:

While the biological science shows how important delta outflow and other environmental protections are for the continued existence of native fish, wildlife and the people who make their homes and living on these natural resources, the political science in favor of increasing diversions and waiving these standards has often trumped the biological science.