Ensconced in my office in Albuquerque, I’ve been popping in and out of the webcast of today’s California State Water Resources Control Board workshop on the future of the Salton Sea, and I’ve noticed a very interesting subtext to the discussion that I think is important. It’s about the importance of Salton Sea environmental management to the broader goals of integrated water management in California and the western United States.

If we’re going to get this right elsewhere, we’ve got to get the Salton Sea question right now.

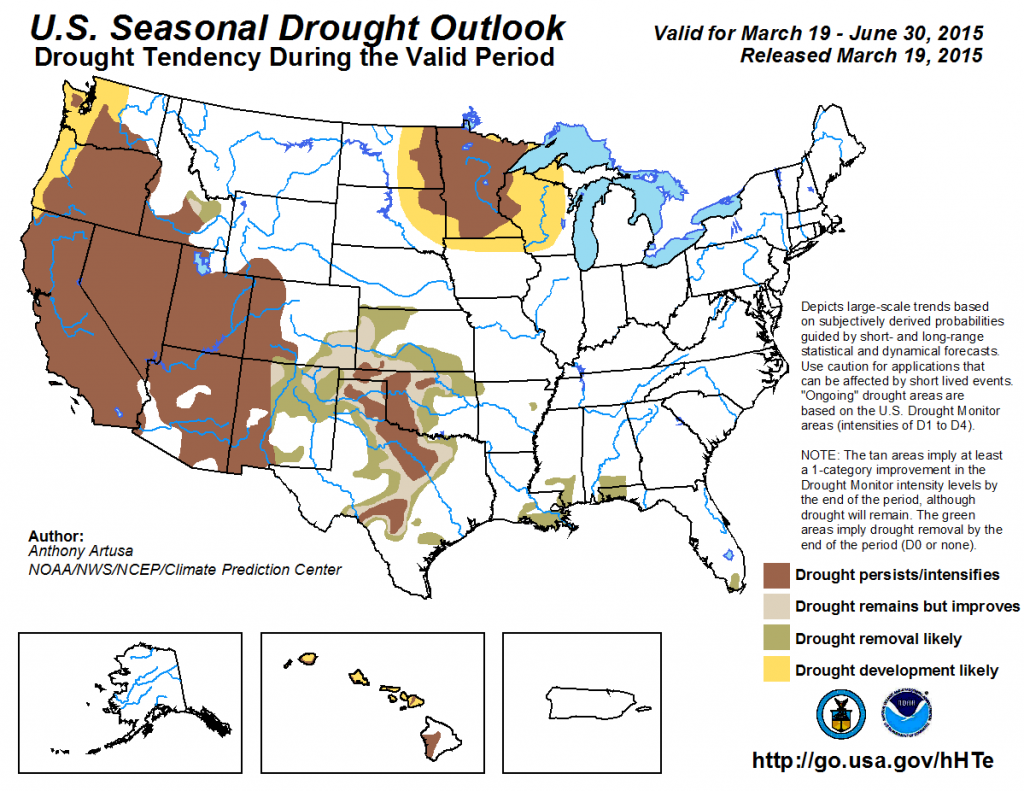

As a broad matter of policy, folks around the West are trying to figure out how to negotiate the process of ag-to-urban water transfers while managing what economists call “externalities” – the third party impacts that we’re going to have to manage as we adjust the system to changing hydrologic and societal realities.

Kevin Kelley of the Imperial Irrigation District told the board’s members this morning that more some 50,000 acres of Imperial farmland was fallowed last year as part of a program by which the metro area of coastal Southern California pays for water conserved. In the midst of a horrific California drought, that water has become critical, making up 60 percent of the municipal supplies shipped down the Colorado River Aqueduct last year, according to Bill Hasencamp of the Metropolitan Water District. That’s huge. We talk about the importance of conservation. This is agricultural water conservation on an enormous scale.

courtesy Kevin Kelley, Imperial Irrigation District

But when agricultural activity in Imperial decreases, that means less ag runoff to feed the Salton Sea, and the sea shrinks. Kelly showed the slide to the right and told the board, “This area was covered in water ten years ago.”

The problem, as the Pacific Institute’s Michael Cohen documented in a report last year, is that drying up the sea comes with enormous costs, as a result of the hazardous dust clouds left behind. Health impacts are likely to be subsantial. Importantly, as several people testified today, that risk falls disproportionately on the poor. Imperial is a very poor place.

That’s bad as a general matter of equity and justice. It’s a moral issue. But it also could be a huge water management problem. The concern, as expressed repeatedly during today’s board meeting, is that as part of the Byzantine water transfer deal that kept Met’s aqueduct full last year with transferred ag water, the state of California promised to deal with “restoration” efforts to mitigate the worst of the sort of consequences Cohen described in his report. That largely has not happened. So LA got its water, Imperial ag got the money in exchange for the transferred water, and the externality remains unaddressed.

Failure here would be a serious setback to other innovated water management efforts, Cohen and his colleagues said in written testimony to the board (pdf):

The State’s failure to provide assurance that it will meet its mitigation obligations – either through a clear, transparent funding plan or through leadership on the development of a vision for Salton Sea restoration/mitigation – will have a chilling effect on future water transfer agreements that require state involvement. In effect, the State’s inaction not only jeopardizes the current QSA, but also diminishes the likelihood that other large-scale water transfers will occur to improve the State’s overall water reliability.

: