tl;dr Everyone on the Colorado River has a legitimate argument that they’ve already sacrificed, and that they have a legal entitlement to what’s left. If everyone digs in their heels on these points, the system will crash. We need to be willing to share the pain. But (scroll to the bottom) there is hope on that front.

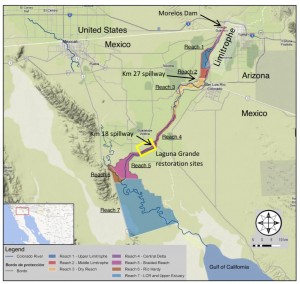

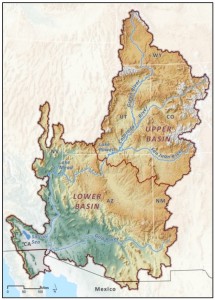

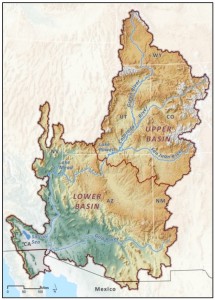

Colorado Basin, map courtesy Pacific Institute

longer – The Unhopeful Part

In reading and interviews for my book, I frequently run across arguments of the form that “we” (usually a state, but also sometimes a smaller water-using entity) have already done “our” share for solving the Colorado River’s problems by (insert specific sacrifice already made here).

They all, of course, are right. Consider:

Arizona

With the 1968 approval of the Colorado River Basin Project Act, Arizona agreed to subordinate the bulk of its Colorado River water rights to California in return for the political supported needed to build the Central Arizona Project, which brings water to Phoenix, Tucson, farms and Native American communities in the central part of the state. As a result, Arizona currently shoulders (at least on paper) much of the risk in the face of shortfalls in the lower basin. Under the current law, all of Arizona’s CAP water would be cut off before California loses a drop. That was a major sacrifice.

California

But wait, didn’t California already lose a bunch of drops? Yup, in 2003 California was cut back from its historical use of in excess of 5 million acre feet per year to 4.4 million. That required major water conservation and supply shifts in metropolitan Southern California, and the fallowing of land in the Imperial Valley to free up enough to keep Southern California’s economic engine humming. So yeah, the next big cuts would hit Arizona if there’s a shortage, but that’s only because California already took a big hit.

Nevada

Nevada took its hit coming out of the starting gate. Its allocation of 300,000 acre feet, which goes to Vegas, is basically a rounding error if you’re rounding total Colorado River flow to the nearest million acre feet. Don’t look at Nevada for sacrifice (and even if you did, as I mentioned, sacrificing Nevada completely is just a rounding error on the Colorado River balance sheet).

Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico

Under the Colorado River Compact, the four states of the Upper Basin are entitled to use 7.5 million acre feet of water per year. When they signed the deal in 1922, they knew it would be a long time before they would grow into their entitlements, but it was water in the bank to support future growth. In 2012, they only used 4.6 million acre feet, which is pretty typical. The Upper Basin states have clearly done their share.

This isn’t cheap sophistry. Each of the above arguments is a reasonably held, legitimate view. It’s most on display this week in the development of Colorado’s water plan:

Colorado wants to ensure its farms, wildlife and rapidly growing cities have enough water in the decades to come. It’s pledging to provide downstream states every gallon they’re legally entitled to, but not a drop more.

“If anybody thought we were going to roll over and say, ‘OK, California, you’re in a really bad drought, you get to use the water that we were going to use,’ they’re mistaken,” said James Eklund, director of the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

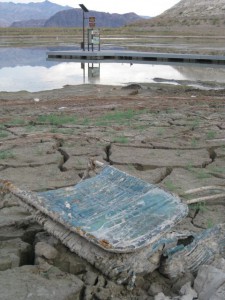

The governance boundary problem

There’s a core issue here that involves the boundaries we draw around our Colorado River water problems. Doug Kenney and his colleagues in the new Colorado River Research Group captured this nicely in one of their first white papers, on “Repairing the Colorado River’s Broken Water Budget” (pdf). Each state, operating within what it thinks are the legal boundaries around its “share” of the Colorado River, has put down on paper a menu of future water options that are wildly unrealistic given the hydrologic reality. There is less wet water in the river than paper water embodied in each user group’s lawyers’ arguments.

Is that realistic? “[I]t’s not, and those water managers that look at the numbers through a basin-wide lens know this,” Kenney and colleagues wrote. But while the Colorado River’s problems have to be solved at a basin scale, much of the water use decision making that matters happens at the state and local level, where the basin wide problems are less visible.

I see this in New Mexico water politics all the time, where there is an expectation that a full firm yield of 96,200 acre feet of water per year through the San Juan-Chama diversion project is our compact-given right. Our sacrifices have been to cleverly live within that allocation, maximizing its beneficial use. The notion that the Colorado Basin as a whole is over-allocated, and that we might have to take a haircut along with everyone else, is simply not part of the discussion.

The hopeful part

To be clear, there are a lot of people up and down the governance ladder, from federal and state to local levels, who aren’t talking this way. Matt Jenkins’ excellent High Country News article today about the Pilot Drought Response Actions program highlights a great example. Here you’ve got a bunch of lower basin water managers trying to find a way to route around this problem, building a couple of different types of institutional widgets to reduce water use locally, but in the context of a basin wide effort.

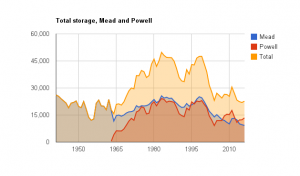

The PDRA (PDRAP?) attempts to overcome the problem Eklund is referring to (If I conserve, won’t it just end up in California?) by matching conservation commitments. The big metro water agencies in each of the lower basin states agrees to take a haircut and leave the saved water in Lake Mead. Arizona, which is clearly the state with the most to lose, pledges 345,000 acre feet by 2017 (the Central Arizona Project is the actor here); Southern California (Met) pledges 300,000 af; Vegas (Southern Nevada Water Authority) pledges 45,000 af and the Bureau of Reclamation agrees to throw in another 50,000 af. The water stays in Lake Mead, to prop up levels and forestall the risk of shortage.

Matt’s story suggests Arizona’s already nailed down a portion of its savings, in the form of ag agency commitments. This is hopeful stuff.