Unless tropical depression Amanda does something miraculous, and quickly, Lake Mead will end May at its lowest level for this point in the year since Elwood Mead and his buddies filled the reservoir in the 1930s, 20 feet in surface elevation below last year at this time.

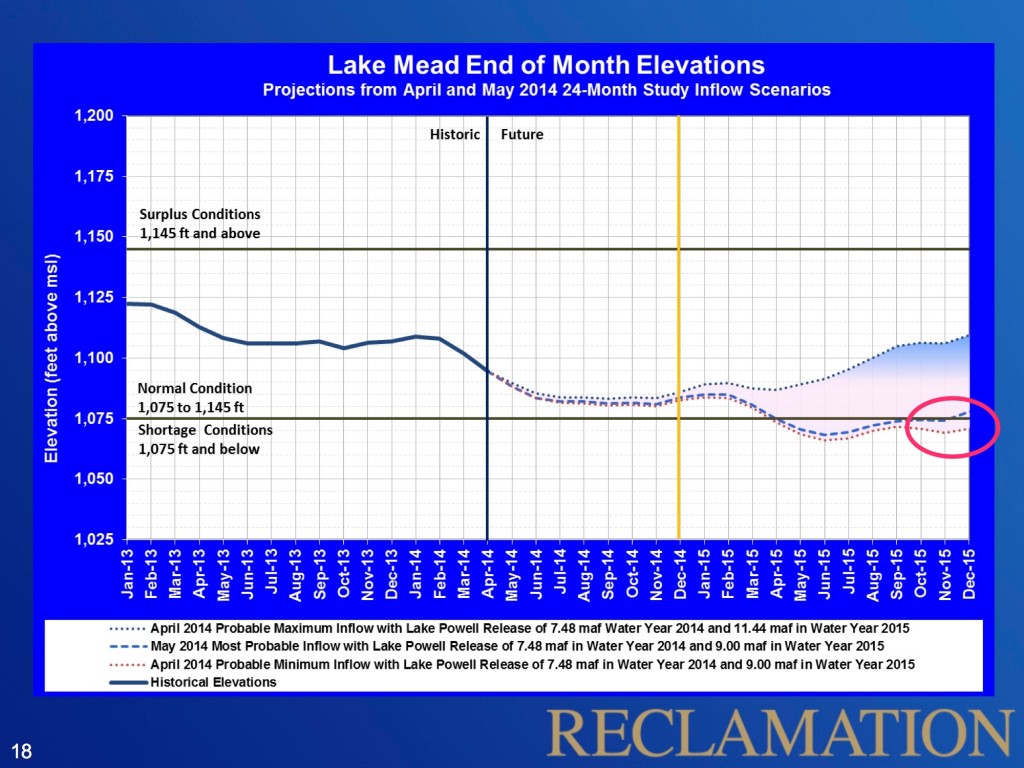

The “tropical storm Amanda” thing was a joke. It would take enough rain to raise Mead’s surface elevation 6 feet to avoid the ignominious record. That will not happen. We are headed into new territory this year in the management of the Lower Colorado River, or “LOCO,” as my new favorite acronym would have it. But it’s not fair to call this, as I did in the first draft of this post, “uncharted territory”. We have some pretty good charts to guide us through this territory. Let’s start here, with the latest estimates presented at this week’s USBR meeting of water managers (pdf):

Based on the current projections, I’ll be able to do this cheap journalistic IT’S THE LOWEST IT’S BEEN THIS MONTH SINCE THEY FILLED IT clickbait schtick pretty much any time I want at least through the end of the water year, Sept. 30.

Why is this happening?

It is tempting to say “drought”, and that’s not wrong. 2014 is likely to end up as just the fifth year in the last 15 with above-average flows in the Upper Colorado River Basin, where most of the river’s water originates. This is a funky bar chart, but ignore the two brown bars, the red one is the most likely 2014 Lake Powell “unregulated inflow” – the amount of water that would flow into Lake Powell if there were no dams or water users upstream. So yes, the system as a whole has been dry.That has resulted in a under-delivery this year of water from upstream into Lake Mead, but as I wrote last summer, the gap here is small, and more than made up for by a massive slug of bonus water delivered in 2011.

But equally important if not more important, the second reason Lake Mead is dropping is because they river’s managers release so much water each year for downstream users. The latest data (pdf) estimate this year’s inflow into Lake Mead at 8.2 million acre feet of water. Combined releases for downstream use in LA, San Diego and Imperial Valley, plus evaporation, plus the water pumped up the hill to Vegas, total 10.4 million acre feet.

The result of all that takes us into the charted territory I was talking about above. That little circle on the right of the first graph – note the dotted red line – shows a real possibility that Lake Mead could end 2015 with a surface elevation below 1,075 feet above sea level. At that point, the first ever shortage would be declared in the lower basin. We have a quite clear roadmap, laid out in the 2007 river management agreement among the basin states. Deliveries to Arizona and Nevada would be cut. (Brett Walton has done a great job of explaining the nitty gritty.)

If all goes well, this would be about the time my book comes out, which would be great for sales. I’ve got some perverse incentives as I watch this play out.