Ringside seats to the decline of Lake Mead

I came away from a week in Las Vegas more hopeful about a deal to prevent a Colorado River crash than I have felt since the ominous day last March when Lake Powell dropped below elevation 3,525.

The annual meeting of the Colorado Water Users Association is a bit like the shadow puppets of Java – projections onto a public stage of things hinted at but largely unseen behind.

On display in public this year, in the formal CRWUA panels, was a frank discussion of the river’s problems that I found unprecedented.

Behind, in the realm of the puppeteers, was even more frank talk about the shape of a deal that would be needed to halt the reservoirs’ declines. It’s still a longshot, with a narrow path to success and a very tight deadline – whatever “consensus plan” the seven Colorado River Basin states come up with has to be delivered to the Department of Interior by the end of January.

But going into CRWUA, I could see no path. Now one is dimly visible.

Managing based on inflow, rather than reservoir levels

A Kuhnian paradigm shift?

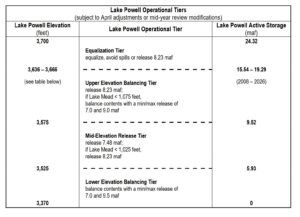

At the heart of the art of the possible here is shift in the discussion of a management framework, from the well-worn path of management by reservoir levels (if Powell “x” and Mead “y”, do “z”) to a system based on inflows. If less water flows in, you have to take less water out.

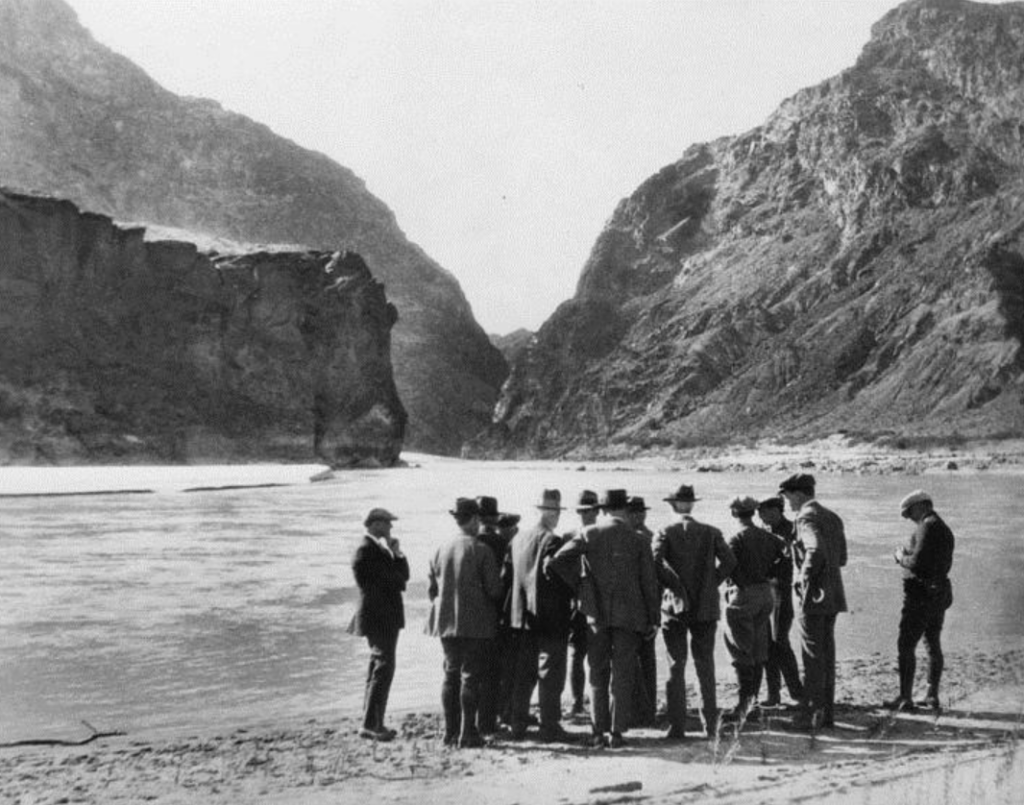

Phrased that way, it sounds so obvious, but it’s a major shift from the way the system was built and has been managed for a century. The reservoirs were built to store surplus when it’s wet to be used when it’s dry. I try not to use the phrase “paradigm shift” loosely, and it’s not entirely clear that it applies here. But the change that we’re seeing bears a lot of the hallmarks of the historian and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn’s original formulation of the concept – the accumulation of enough anomalies that you can no longer stick to the old way of thinking.

I point here, by way of metaphor, to the accumulating shipwrecks emerging from the shores of Lake Mead.

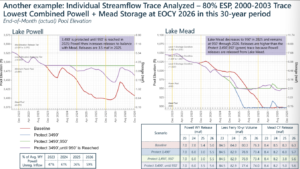

What the hydrologists call the “mass balance problem” makes this inevitable. In the long run, you can’t take more water out of a reservoir than flows in. But the realization earlier this year that Reclamation’s engineers are uncomfortable using Glen Canyon Dam’s lower elevation outlet works has place the mass balance barrier squarely within the range of the next few years’ planning. If you believe them (and, importantly, the Department of Interior seems to), then there’s no way around shifting pretty quickly to a management regime in which the water you release from Lake Powell has to match up each year with the amount that flows in.

So what changes in river management when you shift to an inflow-outflow regime?

As soon as you adopt a policy that says that releases from Lake Powell are essentially limited to what flows into the reservoir – which is the practical equivalent of “protecting elevation 3,490” or whatever line the river management community chooses above that to offer a safety buffer – 3,525 used to be the number people talked about, but we blew right through that last March – you trip two significant management triggers:

- you face the very real prospect of Colorado River flows past Lee Ferry dropping below the 10-year standard set by the compact, triggering either a compromise or a very ugly legal fight

- you face the very real prospect of deep cuts for water users in the Lower Basin, because you pretty quickly turn Lake Mead into an inflow-outflow system too – and/or very ugly legal fights

I could have written all of that before CRWUA began. In fact, I did.

But going into CRWUA I believed the only way to tackle those problems was with a federal intervention. Now there seems a hope of a collaborative solution – of which I’m a big fan.

Relaxing the Lee Ferry Constraint

There were encouraging signs this week that compromise might be possible on the first point, that the Lower Basin might agree to look the other way at a Lee Ferry shortfall, if the Upper Basin states are willing to get past their “it’s a Lower Basin overuse problem” mantra of recent years and kick in some reductions of their own. My read on the situation is that it won’t take a lot of water – folks in the Lower Basin get the fact that it’s primarily their problem. But I’m not in the negotiating room. This will almost certainly be harder than my usual naively optimistic expectation, right?

Cutting Lower Basin Use

Regardless of how the Lee Ferry thing plays out, the hydrologic reality is that there will have to be deep Lower Basin cuts – far deeper than anything contemplated to date. The fact that extreme scenarios are being discussed among the states, rather than having state officials step aside and make the federal government impose them (or, in reality, as newly named Upper Colorado River Commission member Anne Castle reminded us, having climate change impose them) was encouraging to see in the shadows of the CRWUA puppets visible to us outsiders.

That’s incredibly important to the Lee Ferry point, because if the Lower Basin can get together and take on the herculean task of coming up with a formula to agree to the necessary cuts rather than having them be imposed, the Upper Basin is more likely to be willing to contribute without their longstanding worry that anything they kick in will just be sucked up and used in the Lower Basin.

In other words, legitimate action by the Lower Basin states makes Upper Basin action more possible.

My twinkly collaboration fanboy smile should not mislead you into thinking this will be painless – there will be a lot less water for cities and agriculture, and it would be a legal and moral failing if Tribal sovereigns are not brought into this discussion. All of those things make this really hard.

What Happens Next

All of this – an implicit relaxation of the Lee Ferry constraint, voluntary deep cuts in the Lower Basin, and an Upper Basin commitment to contribute some water – seemed to me beyond reach before we gathered at CRWUA. But behind the scenes there was serious, good faith attention to all of them, without the people making the proposals getting laughed out of the room. As Southern Nevada’s John Entsminger told the Nevada Independent’s Daniel Rothberg, the basin states are “still fairly far away from coming to consensus, but we’re closer than we were on Monday.”

Responses to Interior’s request for comments on its crisis-management-in-real-time planning effort are due Tuesday. It will be interesting to see if any of the Basin States offer up a formal first pass at a plan. And Reclamation has asked the states to provide a consensus scheme by the end of January.

Heading into CRWUA, I believed no such consensus was possible. I’ve updated my priors.