Mark suggests an even greener alternative for my riding mower fetish:

Some conversion required.

The water-energy interface is a problem area. Energy production requires water. Water production requires energy. We don’t have enough of either, which is the makings of a serious problem.

There’s a nice summary of the issue in the March 20 Nature, by Mike Hightower and Suzanne Pierce from Sandia Labs. Nature makes you pay, but the Sandia folks have written a more detailed analysis, which you can find here for free.

I’ll have more in tomorrow’s newspaper, to which I’ll link as soon as it’s up.

A story out of Jerusalem about drought in Israel reminds that the place labels change, but the themes remain:

Israel’s water problem stems from population growth and an improvement in quality of life that brings a greater desire to water lawns and gardens, Schor said. This winter was the fourth that Israel got less than average rain, with only about 50-60 percent of the average in most areas, he said.

Critics of government policy note that agriculture uses a large proportion of Israel’s water, receiving heavily subsidized water rates. Since Israel in any event does not grow much of the food it needs, they say, irrigation for farming should be drastically curtailed.

I love Belshaw.

I love Belshaw.Then from behind us, two rows up, comes this gravelly, hard-core South Side Chicago White Sox voice: “Show me da flag! Show me da flag! Show me da flag! Show me da flag! Show me da flag!”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s “Winters” decision a century ago essentially says native Americans are entitled to the water they need. But “need” here is a pretty squishy thing, and we’re still sort out its implications. Matt Jenkins has a terrific piece in the latest High Country News about the Navajo piece of this puzzle – incredibly insightful in the areas I know a lot about, but also incredibly informative in areas I was not familiar with. Jenkins’ discussions of the differences within the Navajo community about how aggressive to be, and how much water to go after, are fascinating.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s “Winters” decision a century ago essentially says native Americans are entitled to the water they need. But “need” here is a pretty squishy thing, and we’re still sort out its implications. Matt Jenkins has a terrific piece in the latest High Country News about the Navajo piece of this puzzle – incredibly insightful in the areas I know a lot about, but also incredibly informative in areas I was not familiar with. Jenkins’ discussions of the differences within the Navajo community about how aggressive to be, and how much water to go after, are fascinating.

Michael Campana has a nice summary, with commentary.

Communicating with a non-statistical public about issues of variability is enormously difficult. I deal with this all the time with respect to weather. How much warmer (colder) is it today than “normal”?

The Energy Information Agency’s “This Week in Petroleum” had a great discussion of the issue Thursday with respect to the prospect of $4 a gallon gasoline. It’s a huge marker out there, but what do we mean when we talk about $4 a gallon gas? As a practical matter, we’re probably thinking about the first time we see that magic $4 at any gas station anywhere in our field of view. But TWIP nicely sorts out the problem of both spatial and temporal variability associated with the price of gas:

Many recent inquiries have asked about the prospects for $4 per gallon gasoline, but what they are really interested in is if they will be paying $4 per gallon at their gas station. In EIA’s March Short-Term Energy Outlook (STEO), the U.S. monthly average retail regular gasoline price is projected to peak near $3.50 per gallon in May and June. It is important to note, however, that even if the national average monthly gasoline price peaks near that level, it is possible that prices during part of a month, or in some region or at some stations, will cross the $4 per gallon threshold.

Michael Tobis does some nice number-crunching on the true costs of energy:

Michael Tobis does some nice number-crunching on the true costs of energy:

A hundred dollars a barrel. A barrel! Energy is unbelievably cheap.

That’s about six million BTUs. One point seven megawatt hours. With that $100 barrel you can power your laptop for two years. You can ship hundreds of pounds of bananas from Guatemala. You can microwave a hundred and two thousand cups of tea to steaming warmth. You can power the digital clock on your microwave for seven million years!

It’s not that energy is too expensive. It’s that it’s too cheap. It’s made us ridiculously lazy.

Especially worthy of note is Michael’s calculation of the cost of shipping a tomato across the country. Not as much as you might think, and (most importantly) not as much as the cost of getting it home from the market in your car.

Charmed by yesterday’s trip north to see snow, I rode my bike up to the Alameda Bridge today to see the result. You can see from the picture that the Rio Grande at 2,000 cubic feet per second is sufficient to begin overtopping the sandbar island in the middle of the river. Lots more snow up north, lots more water coming down. This is gonna be a fun year.

View Larger Map

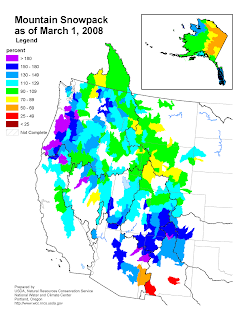

As Scot points out, there’s a crapload of snow all over the western U.S. right now. That’s probably the most interesting bit from a climatological perspective. You typically see wet up north and dry down south, or vice versa. But we’ve also hit a warm spell down here, which means you’re starting to see things melt in a hurry.

As Scot points out, there’s a crapload of snow all over the western U.S. right now. That’s probably the most interesting bit from a climatological perspective. You typically see wet up north and dry down south, or vice versa. But we’ve also hit a warm spell down here, which means you’re starting to see things melt in a hurry.

I took a drive up north yesterday to give it a look. (Turns out Colorado is not that far if your employer’s paying for the gasoline.) If you get up close to a snowbank, you’ll see water dripping off the bottom, forming little rivulets in any low spot, flowing inexorably downstream. Every bit of exposed dirt is muddy right now. The result is the Rio Grande flowing through Albuquerque right now at double the normal rate for March 15. Similar gonzo flow up at Otowi, the main gage for determining Rio Grande Compact legalities, and really big flows on the Chama, where the dam tenders are starting to move water around in preparation for a high runoff year.

I think I’ll go for a bike ride to look at the river.