Eric Kuhn* of the Colorado River District wrote an interesting memo (pdf here) for his board’s meeting next week that lays out the options and reasoning behind current discussions about whether federal legislation will be needed to implement Colorado River Basin drought plans.

The “Law of the River”, which governs allocation, distribution, and management of the Colorado’s water is an interlocking body of statute, compact, treaty, court decision, and executive branch actions that makes tweaks tricky. If you want to do something in one part of the law – say, for example, adjust allocations to respond to drought – you have to be mindful of the impact it has on other areas of the law, even if everyone’s in agreement on the steps to be taken.

At last month’s Colorado River Water Users Association meeting, there was an interesting discussion (during a panel moderated by Eric) of whether federal legislation is needed to implement the various institutional widgets being developed under the rubric of the “Drought Contingency Plan(s)”.

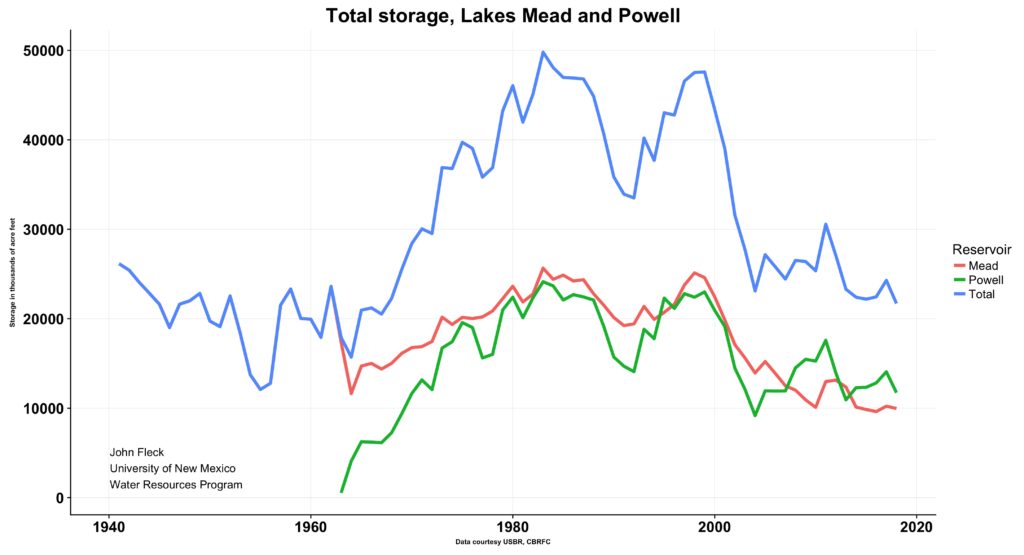

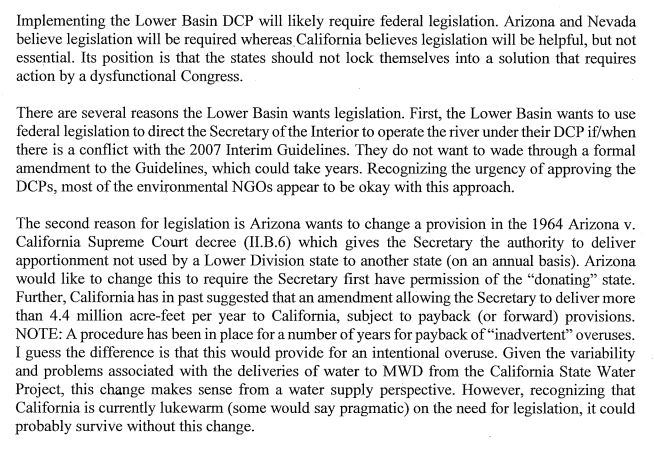

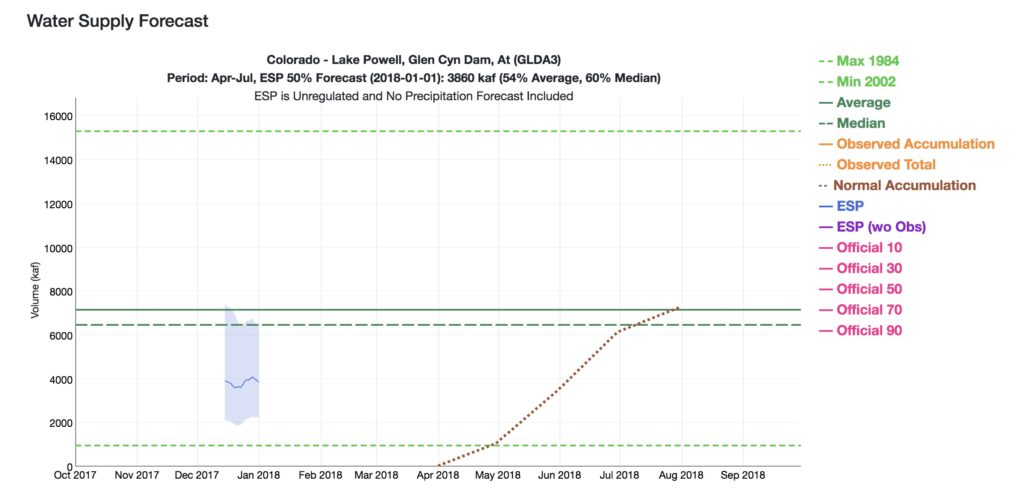

There is a general consensus that legislation will be needed for the Lower Basin part of the DCP, which sets new guidelines for reducing water deliveries from Lake Mead to California, Nevada, and Arizona under conditions of Lake Mead emptiness. Here’s Eric:

Eric Kuhn on the need for federal legislation for Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan

This piece is relatively straightforward, and those favoring this approach say Congress can probably do this in a relatively straightforward, non-controversial way despite its current dysfunction. Simple stuff can still get done.

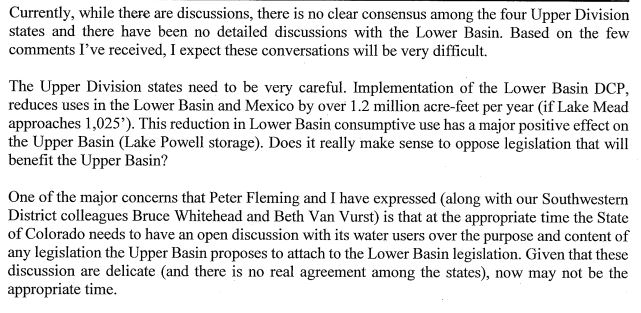

But there are other layers of complexity, including the question of whether, once we unlock the Congressional Action on the Colorado River box, we should take the opportunity to put other stuff in it. Maybe, for example, the states of the Upper Basin should ask for legislation creating a more flexible framework for operating Upper Basin reservoirs to ensure we keep enough water in Lake Powell to avoid compact delivery problems. Eric, in his board member, argues for caution in this regard:

Eric Kuhn on the risks of broader federal legislation for Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan

* Disclosure: Eric and I are collaborating on a book.