I rode a lot this year – for transportation, exercise, and fun. And I GPS all my rides, because FUN!

Here are the year’s rides in and around central Albuquerque.

In the summer of 1931, as the Bureau of Reclamation was launching work on Hoover Dam, flows on the Colorado River dropped to what, at the time, were low flows unprecedented in the few decades’ records on the river. In retrospect it should have been a clue that there was not going to reliably be enough water in the Colorado River to meet the water supply numbers locked into law via the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928

Digging through archives yesterday afternoon for The New Project, I ran across this wonderful headline from the New York Times:

It sits atop a 1932 New York Times letter to the editor from M.J. Dowd, Chief Engineer of the Imperial Irrigation District, which even then I’m pretty sure was the largest user of Colorado River water. Down and his Imperial Valley community really wanted Hoover Dam – to protect from “the flood menace” (“menace” was a common word at the time to describe the river we all know and love).

With Lake Mead now hovering at low levels not seen since its first filling, shortly after Dowd’s optimistic missive, it is perhaps time for a rethinking of his confident premise.

Which, as Eric Kuhn points out in this piece by Luke Runyon on Colorado River “drought contingency planning”, seems to be what is happening:

Kuhn says the Drought Contingency Plan negotiations mark a change in how even the staunchest water managers, often criticized for a narrow focus on claiming as much water as possible and storing it in reservoirs, think about the Colorado River. In the past, he says, conversations were about who would claim the next drop of the river’s water.

“Now we’re talking about when we cut back, which we will probably have to, who’s going to take those cutbacks?” Kuhn says.

At the risk of putting words in Eric’s mouth (disclosure: We’re in the midst of writing a book together, so we’re quite literally in the midst of putting words in one another’s mouths, so to speak.) I think he’d agree that the pivot from conversations about claiming the next drop to talk about how to cut back have been underway since the 1990s. This stuff takes time, but as Eric points out, the current shape of the Drought Contingency Plan suggests most everyone (not all of everyone, knowing side eye glance at Utah) is on board.

We’re up to 82 consecutive days without measurable precipitation at the Albuquerque airport, the 8th longest dry streak in more than a century of record keeping. And there’s nothing in the forecast out seven days, which is as far as it’s reliable to take it (butterfly effect and all). But OK, since you asked, the first glimmer of hope in the really-long-range-don’t-trust-them-but-this-is-just-a-blog-post forecast is Jan. 8., which would put this in the top five dry streaks on record.

Through yesterday, 2017 was tied for the warmest year on record in Albuquerque.

Snowpack in the northern mountains – important for water supply in the coming year – is lousy. The current regression forecast (an automated tool run by the NRCS to provide daily updates based on current snowpack) is just 34 percent of average runoff on the Rio Grande through central New Mexico. You shouldn’t stake a whole lot on forecasts done this early in the year (think of them as more like suggested possibilities – for the stats nerds the forecast at this time of year has an r squared value of 0.45) but neither should they be ignored. Every additional dry day makes it that much harder to catch up.

That said, however, we’re in remarkably good shape right now, the result of both a very good 2017, and significant water conservation and management efforts that leave our human water supply systems in decent shape to weather a bad snowpack.

2017 runoff on the Rio Grande was outstanding – more than a million acre feet of water flowed past the Albuquerque gauge, beneath the Central Avenue bridge. But if you look at the graph to the left, you can also see how unusual a big runoff year is. This was only the third above-average year in the 21st century. “New normal” or whatever, this clearly requires an adjustment.

As a result of the big flow year, reservoir storage is in good shape. Elephant Butte, Abiquiu, El Vado, and Heron combined (the four primary reservoirs on the Rio Grande system in New Mexico) are up a combined ~300,000 acre feet over last year at this time. “Good shape” is relative here – Elephant Butte is still only 20 percent full, far from the glory days of the 1990s. But up is still up, and the Butte is up.

The most interesting thing, to me, is Albuquerque’s aquifer. This is the vast pool of water beneath the metro area, on which we’ve depended for much of the city’s modern life. A shift away from groundwater pumping to the use of surface water from the Colorado River Basin (via the San Juan-Chama Project), combined with significant conservation measures, have led to a rebound that seems unmatched among major urban aquifers in the western United States. Modeling done by the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer suggests aquifer storage is rising by 20,000 acre feet or more a year. Beneath my house, it’s risen more than 30 feet since our 2008 water management shift began.

But that’s the human part. With reservoirs and aquifers and pipes and pumps, the humans will do OK even in the driest of 2018s. The natural systems, not so much. Expect low flows on the Rio Grande to make life very tough for the fish and riparian ecosystem. A year as dry as this is very tough on our mountain forests. And rangeland, whether for natural critters or grazing cattle, could have a very tough year.

The notion of a White Christmas is at best an inventive fiction, at worst a lie. Jody Rosen, in the wonderful book White Christmas: The Story of an American Song, put it thus:

The longing for Christmas snowfall, now keenly felt everywhere from New Hampshire to New Guinea, seems to have originated with Berlin’s song.

Albuquerque’s weather nerds have been playing the “consecutive days without measurable precipitation” game with increasing gusto in recent weeks. It’s up to 79 this morning, this Christmas Eve, which earned it a spot in the top ten such streaks since settler culture brought its particular empirical approach to keeping weather records to this land in the 1890s.

Whether this particular tool kit – a big funnel-like device out at the airport that captures and calculates bulk properties of the drops of rain or flakes of snow that fall upon it – is the best way to understand our current predicament is questionable. But the tools we use to understand our world bias that understanding in unknowable ways, and it’s the tool I know, so every morning I check the length of the streak and tweet.

Washington, D.C. Greyhound bus terminal on the day before Christmas, 1941. John Vachon, FSA/Office of War Information

During my newspaper career, I invented an Albuquerque Journal tradition of the White Christmas story and stuck to it, year after year, because editors are always antsy at this time of year. Antsy editors, in need of copy to fill newspapers, are an opportunity not to be missed.

One of my journalism tricks, in general, was to plant my story in familiar ground, starting with things I imagined readers knew and then lead them from there to new places. And there are few bits of ground as familiar to the American ear than Irving Berlin’s White Christmas:

The sun is shining, the grass is green

The orange and palm trees sway

There’s never been such a day

In Beverly Hills, LA

But it’s December the 24th

And I’m longing to be up north

Wait, what?

The canonical version, the hit sung by Bing Crosby and released in 1942 during the terrifying first year of American involvement in that war, leaves out that first verse. In so doing it leaves aside the tension of a complicated nation with oranges and palm trees and a culture drifted apart from an imagined and, as Rosen argues, never-quite-real past of sleighs and such on a Connecticut farm at Christmas.

But the first verse is always what has charmed me, a life-long resident of the nation’s arid southwestern corner. And so, insulated by reservoir storage, aquifers, and plumbing from any real discomfort associated with 79 days and counting without any rain or snow, I can play the White Christmas game.

LAS VEGAS, NV – When I stopped at Boulder Harbor on Lake Mead Tuesday morning as I drove into Las Vegas, I saw this field of salt cedar taking hold on what had been a mud flat left by Mead’s declining water levels. It’s a clumsy metaphor for what happens when you get comfortable with the levels of a 39 percent full/61 percent empty reservoir.

At this morning’s Colorado River Water Users Association plenary panel, five of the basin’s water management leaders spoke up about the status of the Drought Contingency Plan, the mystical “DCP”. A year ago at this meeting, the DCP seemed close, maybe (I boldly and perhaps naively argued) inevitable. The basic terms – specified water use cutbacks by Nevada, Arizona, and California as Lake Mead drops – have been in place for two years, now it’s just arguing over implementation details.

This year new problems have set in that, the morning panelists made clear, are making this seem harder, not easier. Chief among them is the struggle to get consensus within Arizona about how to accommodate shortfalls on the river, and seems to be getting harder, not easier. “Our challenge is growing, not contracting,” Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke said.

With Arizona an obvious holdout, California has taken a bit of a breather as well, to work out issues involving the Salton Sea, the Sacramento Bay-Delta, and the complicated relationship between the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and Imperial Irrigation District. Met and IID say they are very close, so it seems like once Arizona sorts out its mess, California will be quick to finalize as well.

But that leaves the thorny question of federal legislation. It’s arcane, but there’s a belief among most of the basin states and the federal government that a legislative fix is needed to make DCP work, involving Interior’s authority to manage releases from Lake Mead during drought conditions. And OMG Congress, who wants to ask them to do an important thing right now? And if we do, should we tack on some other things that some of us have wanted to do Congressionally as well, as long as we’ve cracked open that pop-top?

But here’s the thing. Even though we don’t have DCP done, all the basin users are acting, operationally, like it’s a done deal. The states of the Lower Basin are leaving significant quantities of water in Lake Mead this year, kinda like if DCP was already in place. And, crucially, Nevada and Southern California seem to be presuming, in leaving that water in the lake, that the new rules for taking it out under drought conditions, embodied in DCP, will be in effect when they’re needed. Absent DCP, this would pose significant risk for them that they might not be able to get their water out of Lake Mead. This is a strong vote of confidence that DCP, while not done, soon will be.

Those salt cedars growing on Boulder Harbor’s mud flats are operating under the presumption that Lake Mead’s levels are stabilizing. Maybe it’s a vote of confidence in the DCP.

LAS VEGAS, NV – “Dry for Decades,” the tourist placard at Hoover Dam’s Nevada spillway says. “The last time the waters of the Colorado River flowed through this spillway was in 1983.”

LAS VEGAS, NV – “Dry for Decades,” the tourist placard at Hoover Dam’s Nevada spillway says. “The last time the waters of the Colorado River flowed through this spillway was in 1983.”

On my way to this year’s annual meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association, I spent some time yesterday at Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, the great reservoir that stores water for Las Vegas, central Arizona, Southern California, and Mexico.

The reservoir was at elevation 1,081.5 feet above sea level, which in another time would have set off alarm bells in the water management community. But in the years since 2010, when Mead first dropped into alarm bell territory, the sound of the warnings has become muted. In 2010, Mead in the low 1,080’s felt dire. But in the years since, for better or worse, the river management community has become accustomed to operating under the constraints of low reservoirs.

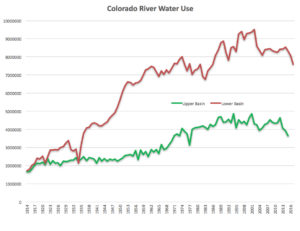

Colorado River water use, data USBR, graph by John Fleck, University of New Mexico Water Resources Program

The “for better” part of this is the increasingly sophisticated operations skill set, the juggling of levels between the various reservoirs on the Colorado River to keep the system operating, and the remarkable conservation success, especially in the Lower Basin, that has stabilized Mead’s levels in the 1,070’s to 1,080’s, at least for now. The latter is remarkable. Lower Basin use of Colorado River water – in Arizona, Nevada, and California – is on track to end the calendar year at 6.7 million acre feet, its lowest since 1986.

The “for worse” part of becoming accustomed to Lake Mead’s bathtub ring and the math that goes with it is the waning sense of urgency.

Policy happens in the hallways at CRWUA, which in this case was a striking conversation outside the elevators last night at Caesar’s Palace as a clog of basin water managers formed on their way to dinner, blocking the hallway so that every new water manager who walked past had no choice but to stop and join the conversation. I’m not a journalist any more, so I’ll happily leave the details unsaid – folks need space to work this stuff out, and I’m confident that they’re trying. But in general, the conversation included two key elements. The first was an enumeration of the various stumbling blocks in the way of a new Drought Contingency Plan, the almost-but-not-quite-done scheme to rejigger Colorado River water allocation and management in times of shortage. The basic terms of the deal have been set for two years, but there are a lot of niggling details.

Folks were very close a year ago at CRWUA to signing the deal. But then we had a reasonably wet winter, the big reservoirs rose a bit, and the pressure was off.

In the classic Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, the political scientist John Kingdon describes how policy entrepreneurs work and refine their ideas, awaiting the convergence of problems and politics to open a window of opportunity. One example of how that might happen is when the problem gets bad enough – say, for example, a plummeting reservoir – that the issue rises onto the action agenda.

So it is not surprising that one of the questions that came up in the Caesar’s Palace hallway, outside the Palace Tower elevators, was the question of what would happen if we had a bad snowpack this winter. At that point, a Kingdon-style “policy window” will likely open. You could think of CRWUA as a gathering of the policy entrepreneurs, preparing for that moment.

Lake Mead is currently 39 percent full (or 61 percent empty, as one wag said in reply when I tweeted about this yesterday). Interesting to ponder what the trigger point is for action.

Laura Bliss turned to Joan Didion today to help make sense of Santa Anas, and fires, in our beloved Southern California:

For all the praise of its “perfect weather,” L.A. is often seen as a city created in defiance of the laws of nature. Before flooded Houston acquired a similar reputation, critics argued that parched, hilly, quake-prone Los Angeles should never have been built where it is: The land is too dry, the earth too unstable. In pop culture, the hubris of its existence brings spectacular punishment—witness L.A. split open by earthquakes, destroyed in alien attacks, consumed by fire. Dubbed the “Devil Winds” in legend and literature, the Santa Ana is an old fixture of this trope, mythicized as a force of insanity, murder,and suicide. “The violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability,” Joan Didion wrote in Slouching Toward Bethlehem. “The wind shows us how close to the edge we are.”

Writing for the Atlantic’s CityLab, Bliss talks of viewpoints, and lessons:

For those in East Coast cities in particular, perhaps, it will stir up a certain moralism about where cities should and should not be—reminiscent, perhaps, of how hurricane damage was often characterized as karma for overdevelopment in Florida and Texas. Why were people living there to begin with?

Undoubtedly, California’s fires have lessons for urban planners: Some of the foothill communities burning this week have recently developed further into the wild-land interface, inserting homes into fire-prone areas. Zoning and other land-use policies may need to be reexamined, among other ways leaders must prepare for and mitigate the effects of an always-burning future, as the warming atmosphere fans Santa Ana flames.

And Faith Kearns, with Didion as well, in a smart take on how this year’s California fires are undermining our sense that we’re in charge:

There is no doubt that this disaster has deeply tested our assumptions about how we live with wildfires, notably the idea that we can control them. From Houston to Puerto Rico to here at home in California, disasters are revealing new ground that is paradoxically both shakier and more solid than it once seemed. We may find our footing by finally embracing the fact that we can’t always be in charge.

And this, which it took a bit for me to dredge from distant memory. It’s from John Rechy’s L.A. novel Bodies and Souls, in which the Santa Anas and their fires were a sort of central character: