Chuck Cullom, the Central Arizona Project’s Colorado River Programs Manager, asked a great question during my lunch talk last week at the Universities Council on Water Resources annual meeting. It was a panel with me and Bill and Rosemarie Alley, who’ve written a new book on groundwater that you should click on this link and buy because groundwater is really important. I’m paraphrasing badly (sorry Chuck), but Cullom wanted our thoughts on how environmental narratives had changed in the last few decades, as compared to the world in which our books now live.

Bill’s answer was brief – no one was writing much about groundwater three decades ago, he said, (or if they were got relatively little attention?) which is why books like the Alley’s are needed. But I’ve injected myself, awkwardly, into a long non-fiction literary tradition that has received no shortage of attention.

When I was a young newspaper reporter writing about Southern California water in the late 1980s, Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert changed the direction of my life.

Reisner, whose book carried the ominous subtitle The American West and its Disappearing Water, tells a gripping story – a tale of skullduggery and hubris in overbuilding the great water systems that became a dominant narrative, framing the fragility of our life in the western United States. Its implicit forecast was that we were doomed to an inevitable crash. That narrative dominated my journalistic life as a newspaper reporter writing about water. First in Southern California and then for more than two decades in Albuquerque, New Mexico, I wrote about water in the sort of places Reisner was describing – improbable cities in the desert built on water imported from elsewhere, fragile, at risk of collapse.

Writing a book is an extraordinary act of hubris: “I have something to say, please spend money for it and then spend hours reading it.” The notion I quietly harbored that we needed the next Cadillac Desert, that it needed an update, and that I might write it, seemed hubris squared. It is one of the great books of the American environmental canon. Who was I?

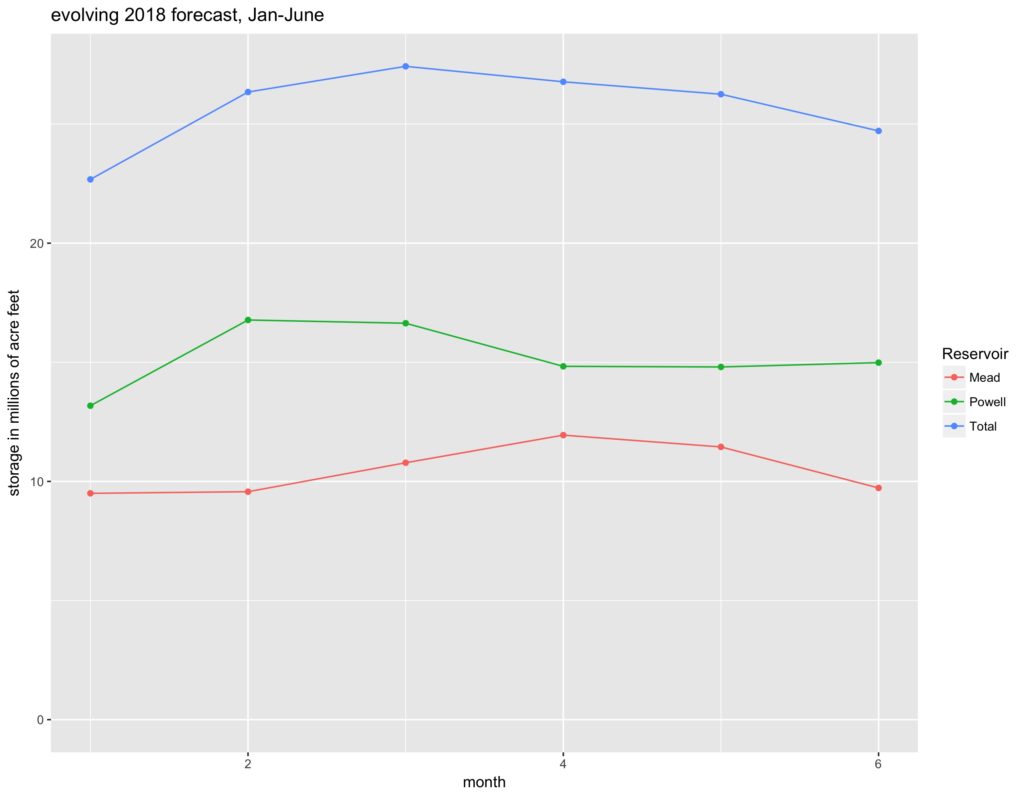

But as drought and climate change sapped the water supplies of these great cities and the farming empires around them in the first decades of the 21st century, my journalism led me to confront a reality even more daunting – that the narrative Cadillac Desert had left us was wrong. People were not running out of water. Instead, they were adapting with remarkable grace and adaptability to this new reality. In Southern California, municipal water use in 2015 was the lowest it has been since 1991, even as population has grown 23 percent. In my hometown of Albuquerque, water use is the lowest since the 1980s. Economists call this phenomenon “decoupling” – efficiency overtaking growth. Agricultural productivity on the farms of California’s Imperial Valley, the largest patch of irrigated ground in the Colorado River Basin, is going up even as the farmers’ water use goes down.

When people have less water, I came to realize, they show a remarkable adaptability. They use less water.

This was now not simply the hubris of writing any book, or even the hubris squared of attempting a sequel to one of the great books of the American canon. I was now attempting to move Cadillac Desert, which had shaped my life, from its dominant place on the American bookshelf.

My University of New Mexico friend and colleague Melinda Harm Benson does a great job discussing the need for this transition here. Benson’s policy nerdery looks hard at the institutions that arise from the “tragedy narrative” of the likes of Reisner, arguing they are ill-suited to meet the challenges we now face. “A fear-based discourse,” she writes, “tends to have a limited shelf life and a narrow window of opportunity.”

OtPR argues that Reisner himself deserves much credit. In so powerfully pointing out our problems, she says, Cadillac Desert “rendered itself obsolete”. It is possible, invoking Benson’s observation, that the “fear-based discourse” triggered by Reisner and others had its moment and had its beneficial effect. (Not sure how we might test this hypothesis? Would this have happened anyway?) The problem now is that its narrative persists long past its best-used-by date. In much of our discourse about water in the West, a narrative of conflict and doom, of “disappearing water”, remains. On the 30th-plus anniversary of the book’s publication, it is time to both honor its contributions, but to also think hard about this new narrative.

As Eric Kuhn helpfully pointed out to me when I was in the final throes of writing the book, my critique of Reisner may have been unfair. The book’s subtitle – “Disappearing Water” – doesn’t quite match the bulk of the text. Here’s the bit I rewrote based on Eric’s comments:

In fact, Reisner concentrated his fierce critique on what he saw as a corrupt process that overbuilt the West’s great plumbing system. The subtitle notwithstanding, Cadillac Desert spends little time on the “disappearing water,” or the actual human consequences of water shortages. But neither did Reisner shy away from apocalyptic rhetoric. In the 1993 afterword to the book’s second edition, Reisner was explicit. California had just experienced what was at the time its worst drought on record, which, Reisner said, “qualifies best as punishment meted out to an impudent culture by an indignant God.”

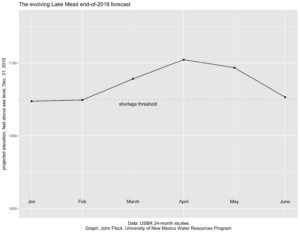

The sportswriter Andy McCullough described his writing life, to paraphrase slightly, as vacillating between unbearable arrogance and crushing self-doubt. That’s the way I felt standing at Hoover Dam watching Lake Mead drop (again and again I have done this). That’s the way I felt riding up the dry sandy bed of the Colorado River three years ago with Juan Hernandez looking for water as the Colorado River crept toward its desiccated delta. That’s the way I’ve felt for the last year as my book emerged into the world.