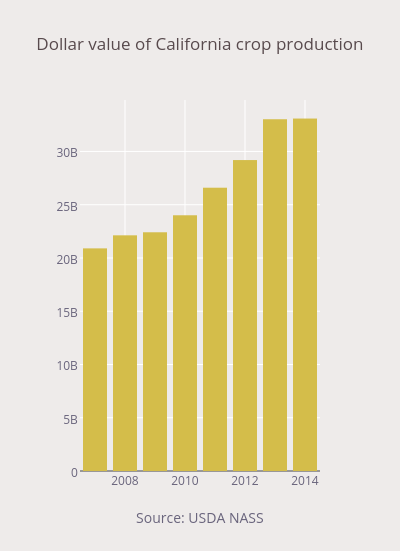

USDA estimates of revenue from California crop production (excluding horticulture) in recent years. I know just enough about this data to be misleading or dangerous, so I make no claims, but it sure seems interesting. Source: USDA NASS

Pat Mulroy and “the tragedy of the anticommons”

Lea-Rachel Kosnick, in a paper a few years back, described the “tragedy of the anticommons”. In a classic “tragedy of the commons,” every pumper is sticking their straw into an aquifer and sucking it out, with no incentive to conserve because the other folks will just take the rest anyway. In the “anticommons” example, there are sane solutions out there, but too many people are positioned to block them.

The commons can lead to the “Tragedy of the Commons,” where uncoordinated utilization of a good can lead to its overuse, and symmetrically, the anticommons can lead to the “Tragedy of the Anticommons,” where poor collective management can lead to suboptimal use of the resource.

Pat Mulroy, former head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, pointedly raised this problem at the March 19 California Water Policy Forum:

We are very, very good at blocking. Anybody can stop anything. What we can’t do or can’t seem to do is find a structure within which to say yes. You will never have enough science, you will never have enough data, but at some point, something has to change.

Huge thanks to Chris Austin for posting the text of Mulroy’s remarks, which as usual are interesting throughout.

John Wesley Powell and climate assessment, then and now

An interesting paper compares the 19th century work of John Wesley Powell in measuring the climate of the West, and suggesting policy responses, with 21st century efforts to assess and advise with respect to climate change. Powell argued for constraints on development while the science needed to better understand the region was carried out. It did not go well:

The language of this early debate is familiar in the context of the current debate. Powell and the irrigation survey were accused of producing scientific information that “… is consistent only the practice of public fraud….” Further, opponents claimed that the ends for the work of Powell was not the improvement of public welfare but the development of a larger political-scientific monopoly run with machine politics methods.

That is from A historical perspective on climate change assessment, K. John Holmes, Climatic Change

March 2015, Volume 129, Issue 1-2, pp 351-361.

Western water visualization

Dean Farr Farrell has made a great visualization tool of western U.S. reservoir levels.

Water in the West MOOC

Anne Gold and Eric Gordon at the University of Colorado are doing what looks like a very cool MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) on Water in the West:

We begin our journey with an overview of the geography of the Interior West and its extreme contrasts, from snow-capped high mountain peaks to bone-dry deserts. We will then look at how humans have learned to adapt to the peculiarities of life in such a dry place as we examine the history of water development in the region and the main legal, political, and cultural issues at stake. We’ll explore the primary role of snow as a water source as we discuss the physical science of water in the west—where it comes from, how it gets used, and how a warming climate could affect its availability.

We’ll use the Colorado River, often referred to as the most controlled and most litigated river in the world, as an in-depth case study.

jfleck’s water news – are we over we overreacting to California drought?

Succeeded in hitting my Monday morning target for this week’s water news.

One of my readers complained that I’m writing too much to keep up with these days (I’ve got a lot of ideas, which I bake halfway and then slop onto Inkstain. You’re my test market.) The newsletter was an attempt to provide a less hyperactive summary. You can subscribe thus:

New Mexico water policy: on muddling through

My former newspaper colleague Win Quigley came over to the UNM Water Resources Program offices the other day to talk to Bruce Thomson and I about central New Mexico’s water problems and the virtue (or inevitability) of muddling through:

“We know how to do this. Humans are adaptable,” Fleck said. “When people have less water, they use less water.”

(Hard to explain how weird it felt to be on the other side of the microphone/notebook. Kinda nerve-wracking, but fun.)

Farmers aren’t the problem

Aaron Citron, with the Environmental Defense Fund, argues that identifying farmers as our water problem – They use 80 percent of our water! – is wrong:

[F]armers and ranchers are the original environmentalists, water conservationists and land stewards. They have been, and continue to be, among the first to develop innovative water efficiency solutions, and they are already implementing a variety of practices to optimize their water use and adapt to drought and climate change.

On World Water Day, it’s important to remember that farmers are our best hope for solving the global water crisis.

Faced with water shortfalls, Citron argues, farmers are in the best position to drive the innovation we need:

When drought hit Brendon Rockey’s Colorado farm hard seven years ago, he planted cover crops to retain moisture in the soil, which also enhanced the effectiveness of his center pivot irrigation. Since then, Rockey’s pumping costs have decreased – his cumulative annual consumptive use cut nearly in half – while his crop quality increased. His neighbors now come to him for advice on maintaining a productive business through drought.

This is what economists would predict, and what they have identified as happening. It’s one of the things the “crisis” rhetoric about “running out of water” often misses.

a city of questionable allure

There’s a famous 1969 photo by Ernst Haas of Route 66 in Albuquerque, scrubbed by a summer rain, looking east toward the mountains. I’m not smart enough to have been imitating, so this isn’t homage. But if you click on the link (I’m not going to embed the image, respect for copyright) you can see on the right of Haas’s image, just past the traffic light, is the spot where I was standing when I took this.

Hucksters trying to pump up the value of a print a couple of years ago tried to tie the Haas picture to Breaking Bad:

Albuquerque is a city of questionable allure, a desert-washed blip in the landscape of the Land of Enchantment. The city serves as the backdrop to the massively popular TV show Breaking Bad, and in a recent interview with The New York Times, the show’s creator, Vince Gilligan, explains that it was Abuquerque’s “stealth charm” that attracted him to the city, elaborating that one of the city’s greatest assets is the piece of Route 66 that still runs through it, “dotted with old neon motel signs like that great Ernst Haas photo.”

Lissa and I were waiting for the bus when the T-Bird drove by. Warm day, Sunday afternoon, top down, and they looked so happy, about as un-Breaking Bad as an Albuquerque day can get. At least I think. I’ve never seen any Breaking Bad.

Haas is using a very long lens, so his scene is compressed in a way that both is part of what makes it a great picture, and that is also disconcerting when you stand there looking at the scene yourself. My picture, with an 18mm lens, is more like your eye actually sees. A reminder that good photography can distort in useful ways.

I’ve lived my whole life, with the exception of five years away at college, within a mile or two of Route 66. It’s always seemed like a story line of some sort, but I’ve never quite known what to do with it. I’d just be draping my personal story uncomfortably atop Route 66 tourist nostalgia. But I always have loved the idea of Route 66, and having some connection to it, and I guess Haas is always in the back of my mind when I have a camera in my hand on that stretch of Central.

Huron CA, on the brink of running out of water, shows why “one bucket” solutions to California’s water problems don’t fit

The little town of Huron, California (Fresno County, population 7,000) is on the brink of running out of water. Its plight to illustrates a broader point about “running out of water”.

First, its story courtesy of the Central Valley News, which reports that Huron could run out of water by July:

Huron, a rural farming community, receives its water from a direct contract with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Just like farmers around the state, dealing with little water for their crops, the 7,000 people of Huron are facing a similar water crisis….

Last year, Huron received 50 percent of its water allocation bringing it through November, according to Betsy Lichti, district engineer with the Fresno Division of Drinking Water of the State Water Resources Control Board.

This year, Castro said, the outlook is far worse.

In following drought and the resulting water shortfalls, it’s important to be carefully attentive to who, specifically, is at risk of running short of or out of water, and why. The city of Huron, and its comparison to other California municipal and farm water users, illustrates what I think is an important shortcoming of UC Irvine/JPL scientist Jay Famiglietti’s LA Times analysis of California’s water problems. To say California “has about one year of water stored,” (as the revised headline points out), and Jay’s suggested policy response (“immediate mandatory water rationing … across all of the state’s water sectors”) treats “California water” as one giant bucket and suggests a “one giant bucket” solution.

But the Huron story, and a look at other places that aren’t running out, suggests that we’ve really got a thousand smaller buckets in various stages of “running out” (or not). Water management happens at the scale of those thousand buckets. The new Public Policy Institute of California drought report makes this point nicely:

Thanks to substantial investments following the 1987–92 drought—and despite the addition of more than 8 million new residents since that time—most large urban areas have experienced only modest water shortages so far. Drought resilience improvements included new surface and underground storage, new interconnections that enable supply sharing with neighboring agencies, expanded use of recycled wastewater and stormwater, and water purchases. In addition, low-flow plumbing fixtures and appliances and changing behavior have reduced per-capita water use in most urban areas. In contrast, several large communities and numerous small, rural communities relying on a single source (often groundwater) experienced severe shortages. Some required emergency aid from the state.

Huron, dependent on the San Luis Project bucket to deliver its water, didn’t diversify its supply. Now the San Luis bucket is empty, and it’s screwed. Farmers who depend on the San Luis bucket have a bit more flexibility. They can fallow a field if there’s no water to irrigate it. You can’t fallow a city.

There are some water policy moves that have to happen at the scale of the state of California as a whole (the PPIC report suggests a number of good ones), but the hard work of responding to drought has to happen one bucket at a time.