NPR’s Dan Charles had a nice piece on California’s drought this week digging down a layer into how farmers are actually responding to California’s drought.

They are:

- Fallowing fields of annual crops like corn to ensure they have enough water for their permanent crops, like almonds.

Sarah Woolf takes me on a tour of her family’s farm, and points toward one dry field. “It had onions in it last year, and we’re not farming it at all, because we don’t have enough water supply,” she says.

- Pumping groundwater to make up for surface water shortfalls.

According to a new report from the University of California, Davis, the extra water that farmers will pump from their wells this year will make up for about 75 percent of the cutbacks in water from dams and reservoirs.

Of course this cannot go on forever. Groundwater levels are dropping:

Woolf tells me that just this morning, she heard about problems at one of their wells. “We have to actually drill down and drop the well deeper, which is a very bad sign,” she says. It means that the water table is dropping; the aquifer is drying up.

I’m intrigued by the question of how this is different than other extractive human activities that depend on fluctuating availabilities of raw materials needed to do the things we do in a modern world.

Earlier this month, Lissa and I spent days wandering aimlessly around the San Juan Basin, the desert country where the Four Corners states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona meet. It’s an area that lives with the ups and downs of oil and gas production, and it’s been down lately, bypassed by the horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing boom.

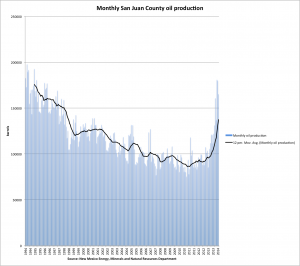

As my Albuquerque Journal colleague Kevin Robinson-Avila has written, there’s a rock layer called the Mancos shale that has shown promise using the new techniques, and as Lissa and I were wandering the back roads, we saw a lot of activity – drill rigs, fancy new oilfield services pickups. And there’s some indication in state data that there’s been an uptick in oil production in New Mexico’s San Juan County in the last six-plus months.

Here’s my question: Why is the societal conversation about the ebbs and flows of one natural resource (water/drought) so different from the other at issue here (oil production)? In both cases you have communities dependent on the resource that rise and fall in response to its availability, and adjust to its presence or lack.

In California’s central valley, farmers adjust to changing water available by adopting new techniques and changed cropping practices. In some cases, as the resource disappears completely (I’m thinking here of depletion of groundwater that can be economically extracted for farming), this particular human activity will simply go away. In other cases, farmers will adapt, shifting cropping patterns, as we’ve seen on the high plains. This looks a lot like an oil and gas economy of the type Lissa and I saw in northwest New Mexico.

I’ve catalogued some similarities here. What are the differences? Why are the societal conversations about the two resource issues so different?

update, Brian Jordan had some comments on twitter:

@jfleck 2/2 I don't think there's as much diff. as suggested…there's a "Peak X" meme for every natl' resource but our selection bias is H2O

— Brian Jordan (@jordanbrianl) May 25, 2014