Trapped in a world we never made.

As we get spun up for the second time in six months about a capricious notion of a “deadline” to fix the Colorado River, I’m reminded of the tagline from my favorite teenage superhero comic, Marvel’s Howard the Duck:

Trapped in a world he never made.

Once again, we are trapped in a narrative driven by a somewhat arbitrary “deadline” that misunderstands the nature of the ongoing processes as the collective community struggles to come up with a plan to save the Colorado River.

About that “deadline”

HTD#1, 1976

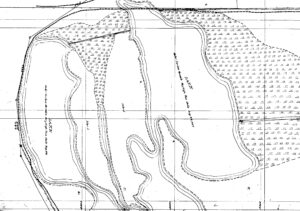

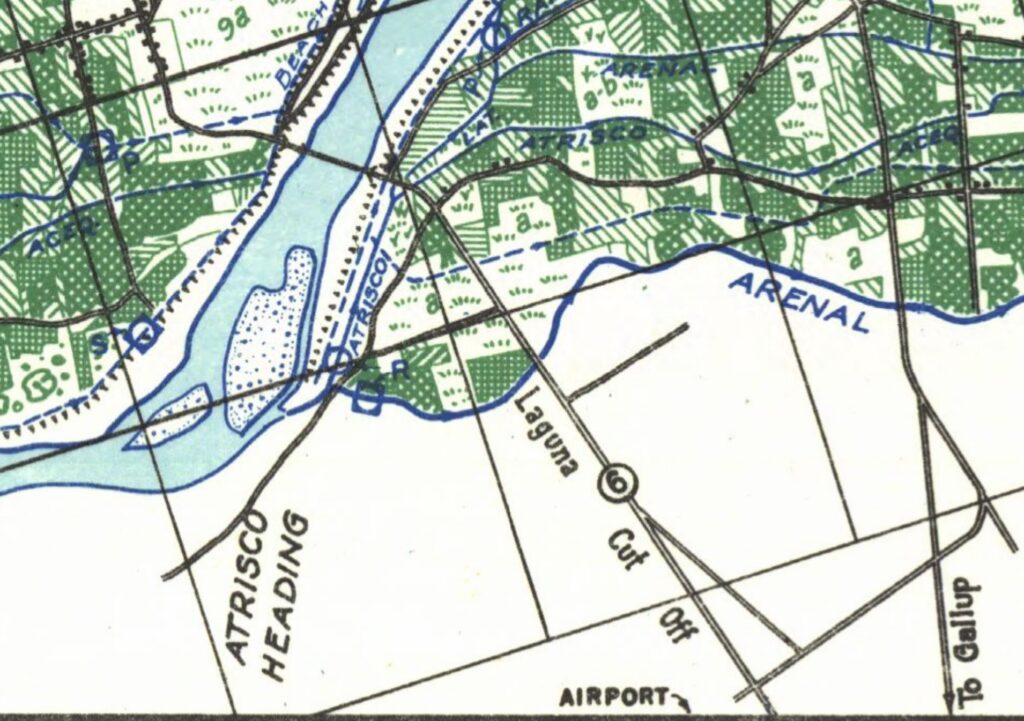

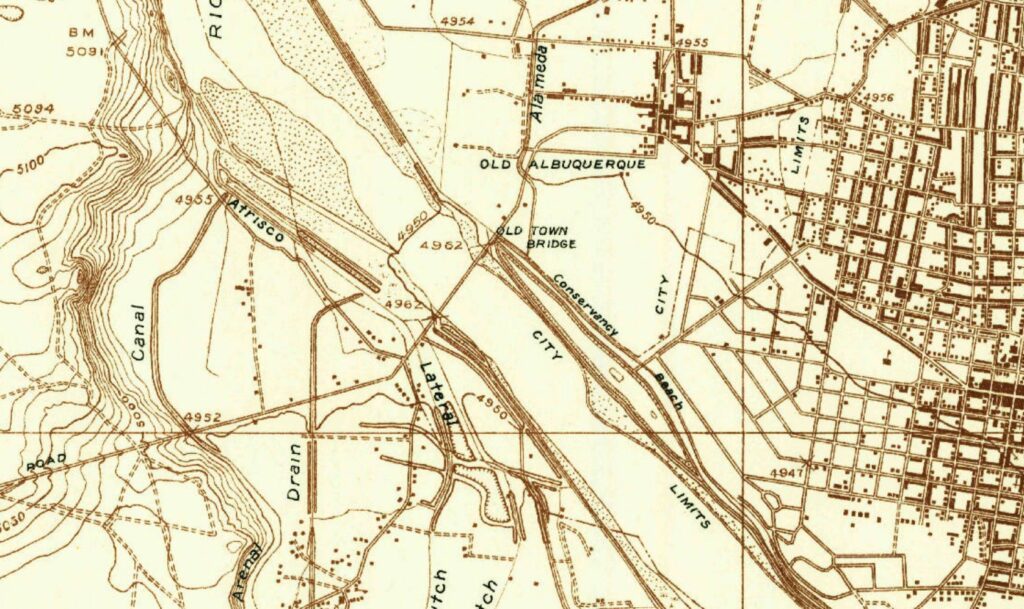

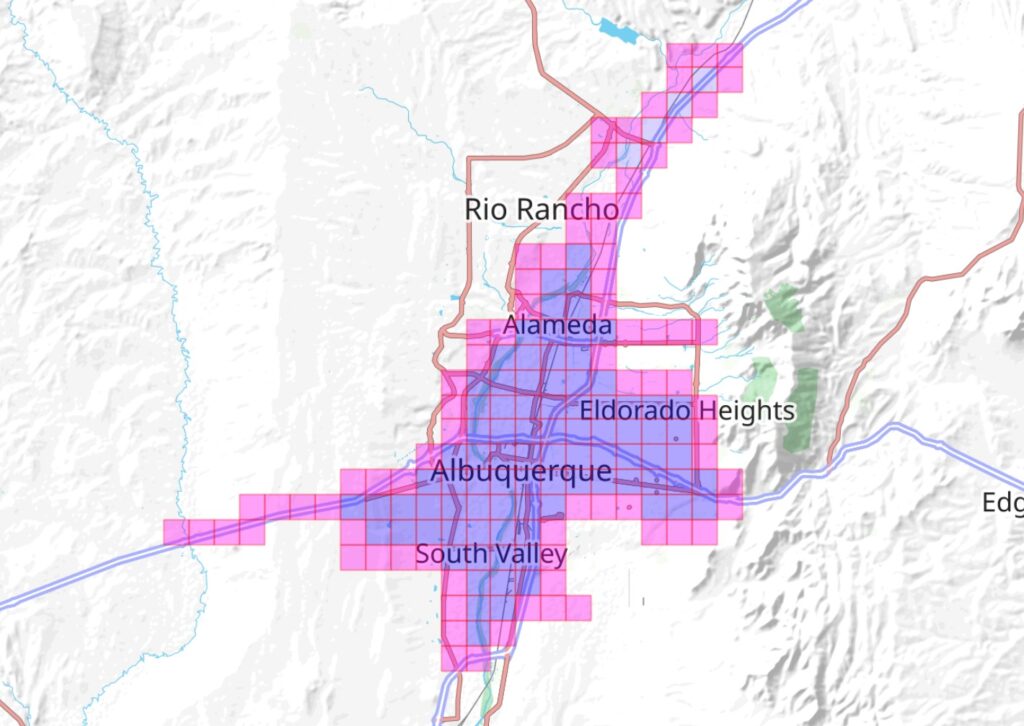

I’ve been absorbed in recent weeks writing about 1920s Albuquerque and the Rio Grande, so I’ve not had the time to do my usual “keep up with Colorado River stuff” that is typically a prominent feature of this blog, requiring me to read stuff and call a bunch of people, kinda like a journalist but as a hobby rather than a job with an editor glaring at me from across the room waiting for me to file.

But it’s been hard to avoid the spun up media attention to next week’s “deadline” for the Basin States to come up with a plan to…. Well, I’m not sure exactly what it needs to do, that’s part of the challenge.

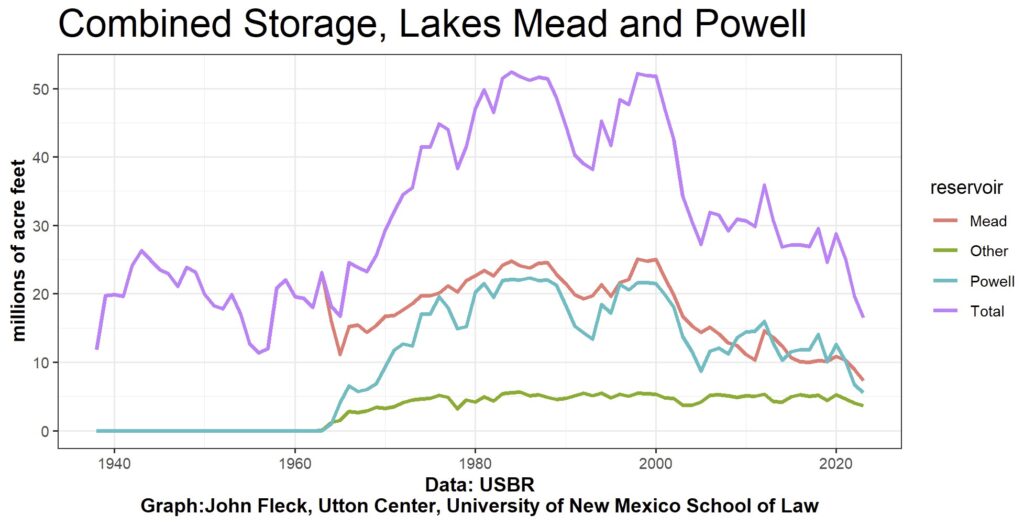

Media coverage demands what we call “news pegs”. A Jan. 31 “deadline” for the seven Colorado River basin states to deliver what we all hoped would be a “consensus proposal” to reduce Lower Basin water use, reduce releases from Glen Canyon Dam to protect the infrastructure there, and save the West, and if the states don’t save themselves the feds will have to step in an impose their authority, provides such a news peg, a thing for reporters to pitch as a news peg to editors. And pitch it they have, with good reason! This is a really important story!

Thus we have Colton Lochhead last Thursday in the Las Vegas Review Journal: “Colorado River water managers optimistic about drought plan as deadline looms.”

Or Christopher Flavelle a day later in the New York Times: “The seven states that rely on the river for water are not expected to reach a deal on cuts. It appears the Biden administration will have to impose reductions.”

Wait, what?

A close read shows that the two stories, despite apparently contradictory headlines, are not inconsistent.

Flavelle’s pointing to the unlikelihood of a seven-state deal, which seems right. The AP’s Kathleen Ronayne did a great job with this part in a piece that ran this weekend:

California says it’s a partner willing to sacrifice, but other states see it as a reluctant participant clinging to a water priority system where it ranks near the top. Arizona and Nevada have long felt they’re unfairly forced to bear the brunt of cuts because of a water rights system developed long ago, a simmering frustration that reared its head during talks.

Thus in all the palavering over the last six months, California has been the odd state out, making it unlikely that you’ll see a seven-state agreement on how to reduce Lower Basin use and juggle releases from Lake Powell to reduce the risk of breaking Glen Canyon Dam.

Lochhead nicely captures this nuance in his story, because there’s nothing magic about a deal all seven states can sign:

Chuck Cullom, executive director of the Upper Colorado River Commission, which is made up of representatives from Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico, said he expects that the states will reach a consensus for submitting a proposal before the Feb. 1 deadline, but whether every state will be able to endorse the approach remains less clear.

Thus we see the foundation for a hilarious conversation I had a few weeks back with one of the players in all of this about the meaning of the word “consensus”. What if something emerges that most of the states like, but not all seven?

Howard the Duck and Interior’s existential dilemma

For the second time in six months, we find our heroes at the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department of the Interior existentially trapped, like Howard, in a world they never made.

By “world they never made” here, I mean the rising frenzy over a deadline next Tuesday after which….

We’ll, I’m not sure what happens after Tuesday, let’s explore….

Why are we all (I’ve been doing this too!) reporting on a looming “deadline”, and concluding that if it is not “met”, as Flavelle reported in the grey lady, the federal government will have to step in and impose cuts? It’s really just a vague marker in a complex timeline needed to get a draft Environmental Impact Statement out by early April, and a final decision document done by summer.

There’s nothing firm about Jan. 31, a magical coach that will turn into a pumpkin if the states don’t agree on a plan by midnight. (One plus of the blog format is that there is no editor across the room glaring at me for mixing Howard the Duck and Cinderella.)

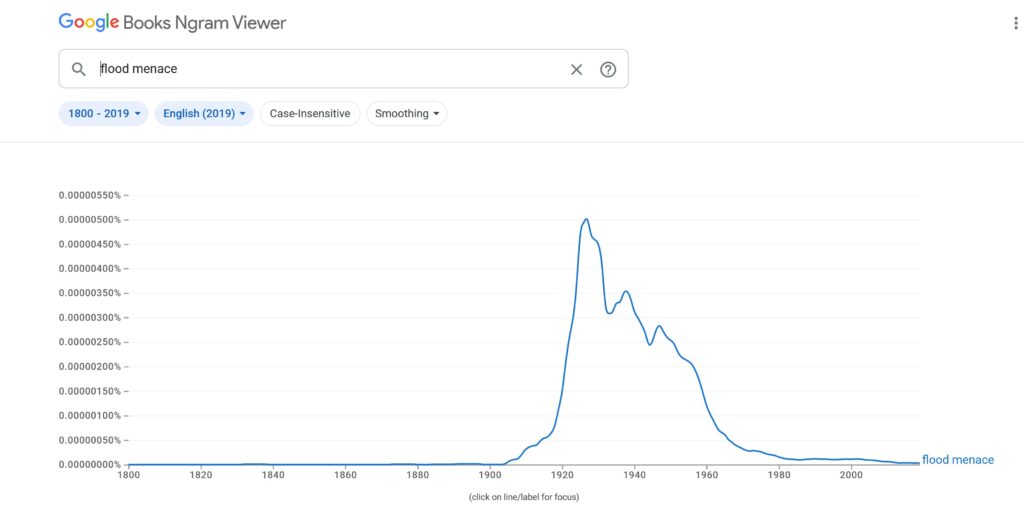

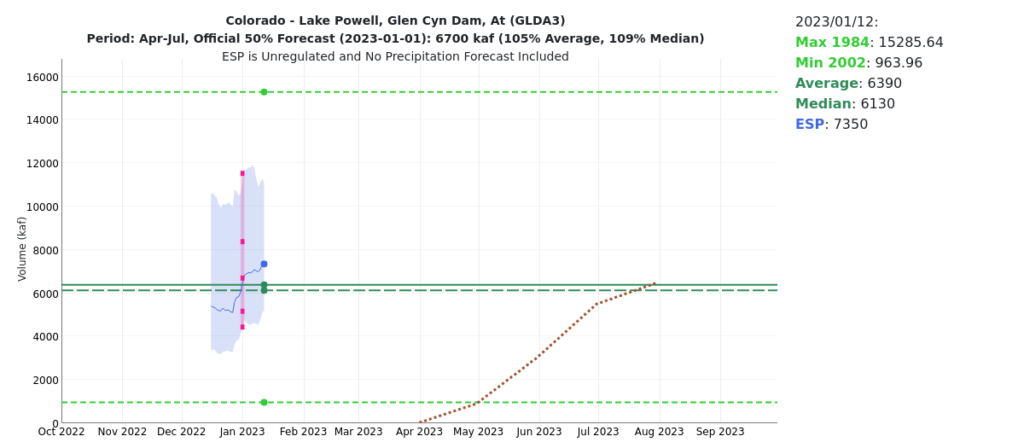

Last summer, the last time we played this game, the idea of a “federal deadline” took on a life of its own, setting off both a flood of stories about a “missed deadline” and a really productive process through the fall and winter that has moved us closer to clarity about what sort of cuts will be needed and how they might be apportioned. The Southern Nevada Water Authority has very publicly presented a proposal worth modeling, which has drawn interest from other states as a foundation for working out the issues. Other states (though not publicly) have offered up proposals of their own.

These exist! Reclamation can model them and tell us how they work under various hydrologic scenarios!

All of these can now be rolled into the modeling efforts being done by Reclamation in the next few months to help us all understand the “if this then that” questions about how we manage the system over the next few years to protect public health and safety and the dams.

Given the current frenzy over a looming “deadline” and the risk of failing to meet it, it’s worth returning to the original language in the Department of Interior’s federal register notice launching this process.

It laid out three scenarios the agency hoped to evaluate.

The first is a “no action” alternative which basically says fuck it, let’s just crash the system.

The second is the one we’re currently all spun up about, so it’s worth reading the actual language of the notice:

Framework Agreement Alternative: This alternative would be developed as an additional consensus-based set of actions that would build on the existing framework for Colorado River Operations. This Alternative would likely build on commitments and obligations developed by the Basin States, Basin Tribes, and non-governmental organizations that were included in the 2019 DCP.

No deadline here, no requirement for all seven states to sign on. Suitably vague, to allow the players the room to move as they try to come up with something workable. Which is what is now happening.

And finally….

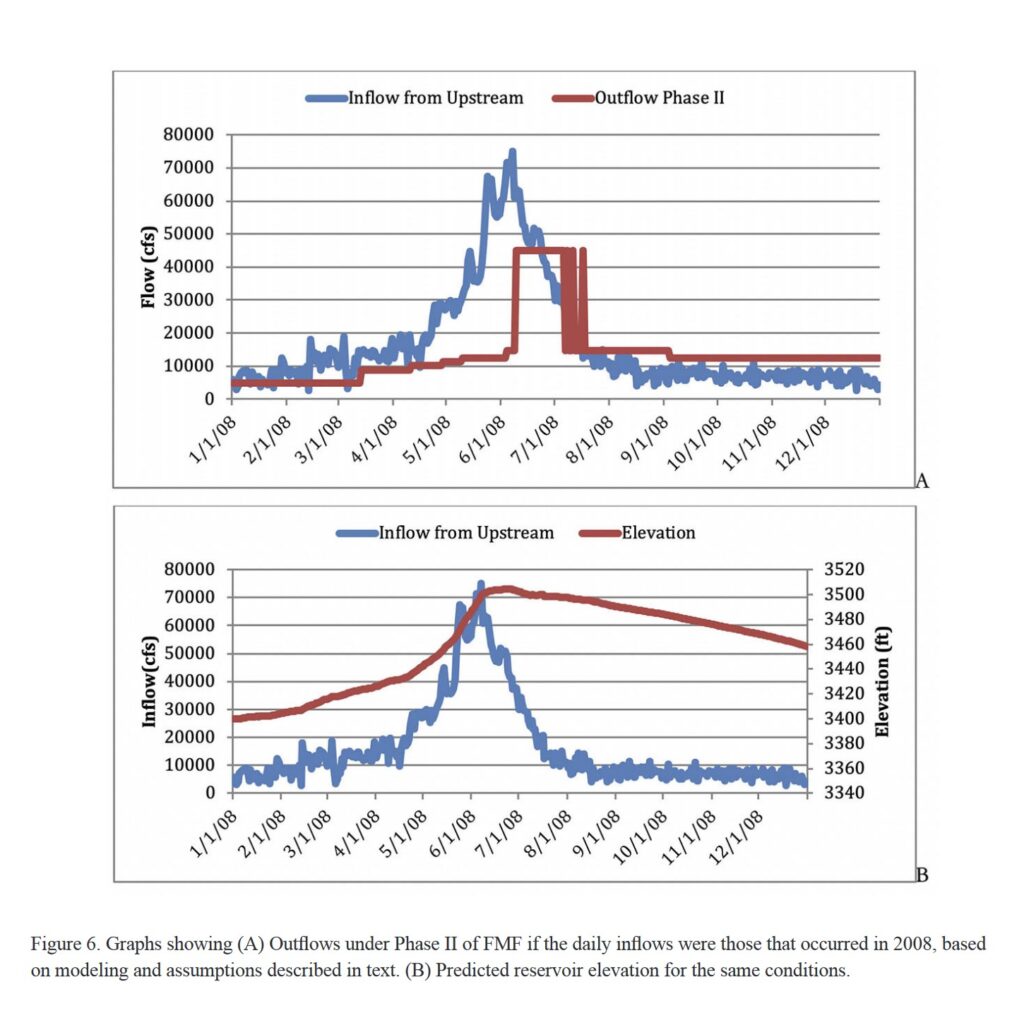

Reservoir Operations Modification Alternative—This alternative would be developed by Reclamation as a set of actions and measures adopted pursuant to Secretarial authority under applicable federal law. This alternative would likely be developed based on the Secretary’s authority under federal law to manage Colorado River infrastructure, as necessary, and would consider any inadequacies or limitations of the consensus-based framework considered in the above alternative. This alternative would consider how the Secretary’s authority could complement a consensus-based alternative that may not sufficiently mitigate current and projected risks to the Colorado River System reservoirs.

Look, I’d be delighted if the seven states had settled on something on which they could all agree and handed it off Tuesday to Interior to model.

Following CRWUA, I was optimistic about the generally favorable response to Southern Nevada’s proposal.

I am discouraged that the continuing tension highlighted in a number of the stories between California’s stubborn insistence on its interpretation of its seniority under the Law of the River and the more adaptable interpretations being suggested by others in response to impacts of climate change unforeseen when the laws were written 60, 80, 100 years ago has made it impossible to get something done by next week. This may be the disagreement that leads us toward litigation and the “no action” alternative, see bad words before about crashing the system.

But it’s clearly not the case that it’s game over for a collaborative solution come Wednesday, that we’ll just leave it to the executive branch of government to save us (the water users across the basin) from ourselves.

The notion of a “deadline” has taken on a life of its own that is clearly unmoored from the reality of what actually needs to be done.

Support Inkstain

I drink coffee. You can help.