Round rocks of the San Juan-Chama project

I had the joy of sharing a goofy group text thread yesterday evening with a couple of friends exchanging pictures of the round rocks we each collected yesterday morning on a field trip to see the plumbing of the San Juan-Chama Project, which diverts Colorado River Basin water beneath the continental divide to bring drinking and irrigation water to New Mexico’s parched middle Rio Grande Valley.

The San Juan-Chama Project’s 25 miles of tunnels are the thread that connects us in central New Mexico’s Rio Grande Basin to water and its management across the Colorado River Basin. That makes the tunnels the thread that holds together the work I’ve been doing for the last decade trying to understand the relationship between the water in my little town of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and the water challenges of the greater West. But I’d weirdly never actually visited this vital bit of plumbing.

So when a friend invited me to tag along Thursday and Friday on a workshop and facility tour for San Juan-Chama Project water users to talk about infrastructure management and governance, I said “yes”.

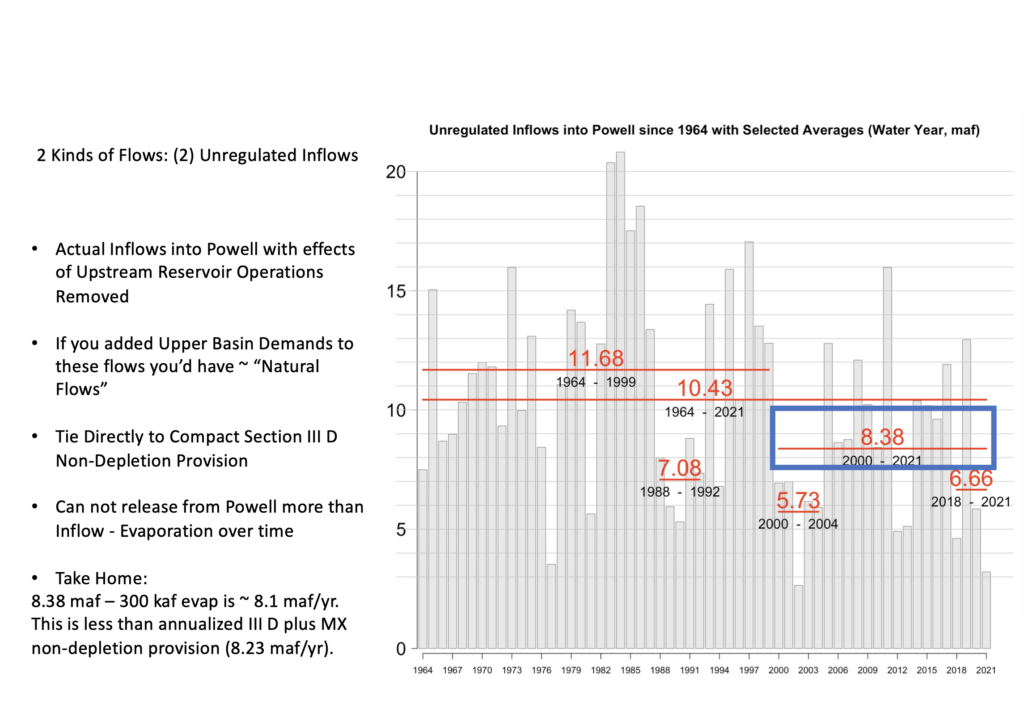

We hung out Thursday afternoon at a lovely picnic shelter along the Rio Chama talking about concrete maintenance priorities and the crazy-sounding Law of the Colorado River governance rules. (The concrete discussion was fun, but I didn’t understand a lot of it. There were a lot of totally legitimate “What, what? Why did they do it that way?” questions about the crazy governance structures.)

Friday we toured the dams and diversions.

the mouth of the Azotea tunnel

When I told WT, one of my former students, that I was headed up to Chama for a facility tour, he told me I had to pick up some round rocks at the Azotea Tunnel. Azotea is where the water emerges from beneath the continental divide after miles of concrete tunnel. Rocks that make it through the intakes have been skittering and rolling for a good long while, like time in a multi-million dollar rock tumbler, before they emerge to be deposited as the water slows and begins its trip down Willow Creek and into the Rio Chama on its way to my Albuquerque faucet.

The group had swollen to about 30 by the time we got to Azotea, with about a dozen mostly white government rigs parked on the apron above the tunnel. And within moments of our arrival, the senior managers from central New Mexico’s largest municipal water agencies had scampered like kids down the rocky channel embankment to begin hunting for the best round rocks.

The headwaters snow is long gone, and the tunnel’s been dry save for a couple of late summer rainstorms since the second week in August, which sucks for water management purposes, but was great for round rock hunting!

The rocks were cool, but the real value was the earnest goofiness of the endeavor.

I write a lot about the importance of “social capital”, the personal bonds among the water management community’s problem solvers. That’s what this was about.

We sat out by the Rio Chama Thursday evening until well after dark, long after the grill had cooled, talking water until it was so dark you could see the Milky Way and the evening star (Venus?) next to a setting sliver of a moon. We artfully arranged the car-sharing arrangements so we had time to talk during the shuttling from one tunnel and diversion dam tour stop to the next. We clustered in the shade eating our salads and PB&J talking about the Green Book and water bypass rules and Sec. 11 of Public Law 87-483, the San Juan-Chama Project’s 1962 authorizing legislation.

We collected round rocks. And then gleefully texted pictures of them with one another after we got home.

Second, it means that it is not helpful to continue to talk about closing the gate. There is a long history of people moving out here to the West and then wanting to turn around and close the gate. Unless you are a Native American and your family has been here since time immemorial, you do not have the moral high ground to close the gate. There’s something like 8 billion people on the planet. Our cities are going to continue to grow.

Second, it means that it is not helpful to continue to talk about closing the gate. There is a long history of people moving out here to the West and then wanting to turn around and close the gate. Unless you are a Native American and your family has been here since time immemorial, you do not have the moral high ground to close the gate. There’s something like 8 billion people on the planet. Our cities are going to continue to grow.