The Upper Colorado River Commission, at its meeting this afternoon (Wed. June 20, 2018) in Santa Fe, voted to end its participation in the Colorado River System Conservation Pilot Program, in which water users, mostly farmers, were compensated for conservation measures in an effort to create “system water”.

“System water” is a tricky concept, and therein lay the problem. Saved water simply stays in the system, flowing down rivers until either a user downstream takes it out themselves, or until it makes its way unmeasured and unaccounted for into Lake Powell, at the bottom of the Upper Basin. This is great! Leaving water in rivers, eventually getting it to Lake Powell, is a good thing! But not having an accounting system to track who put it there makes its use in long term management of the Upper Basin’s obligations under the Colorado River Compact problematic, removing the big incentive for people to do it in the first place. “Any water that is currently conserved,” the UCRC resolution explained, “is subject to use by downstream water users or release from existing system storage prior to being needed in response to emergency drought conditions, thereby defeating the intended purposes of Demand Management.”

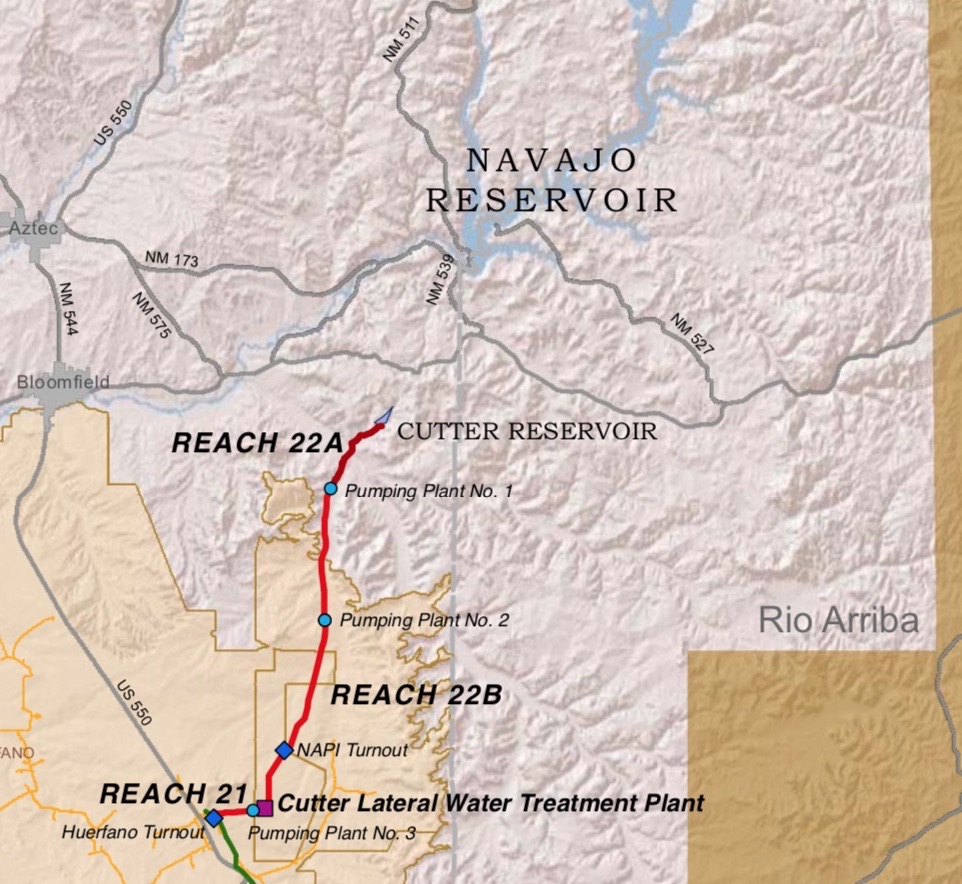

(l-r) Felicity Hannay, Amy Haas, Don Ostler, and Karen Kwon at the June 20, 2018 meeting of the Upper Colorado River Commission. It was Ostler’s last meeting as UCRC executive director. Haas takes over the position July 1.

“It does not,” said the UCRC’s resolution approved this afternoon, “provide a means for the Upper Division States to account, store, and release conserved water in a way which will help assure full compliance with the Colorado River Compact in times of drought.”

This highlights a thorny but common water management dilemma – whose water is conserved water. Bruce Lankford has dubbed this problem the “paracommons” (I wrote about it here, in a blog post that was a rough draft for the explanation of this issue in my book). Here’s Lankford:

In a scarce world, society is increasingly interested in the efficiency of resource use; how to get more from less. Yet if you ‘save’ a resource, what does that mean and who gets the ‘saved’ resource? In other words who gets the gain of an efficiency gain?

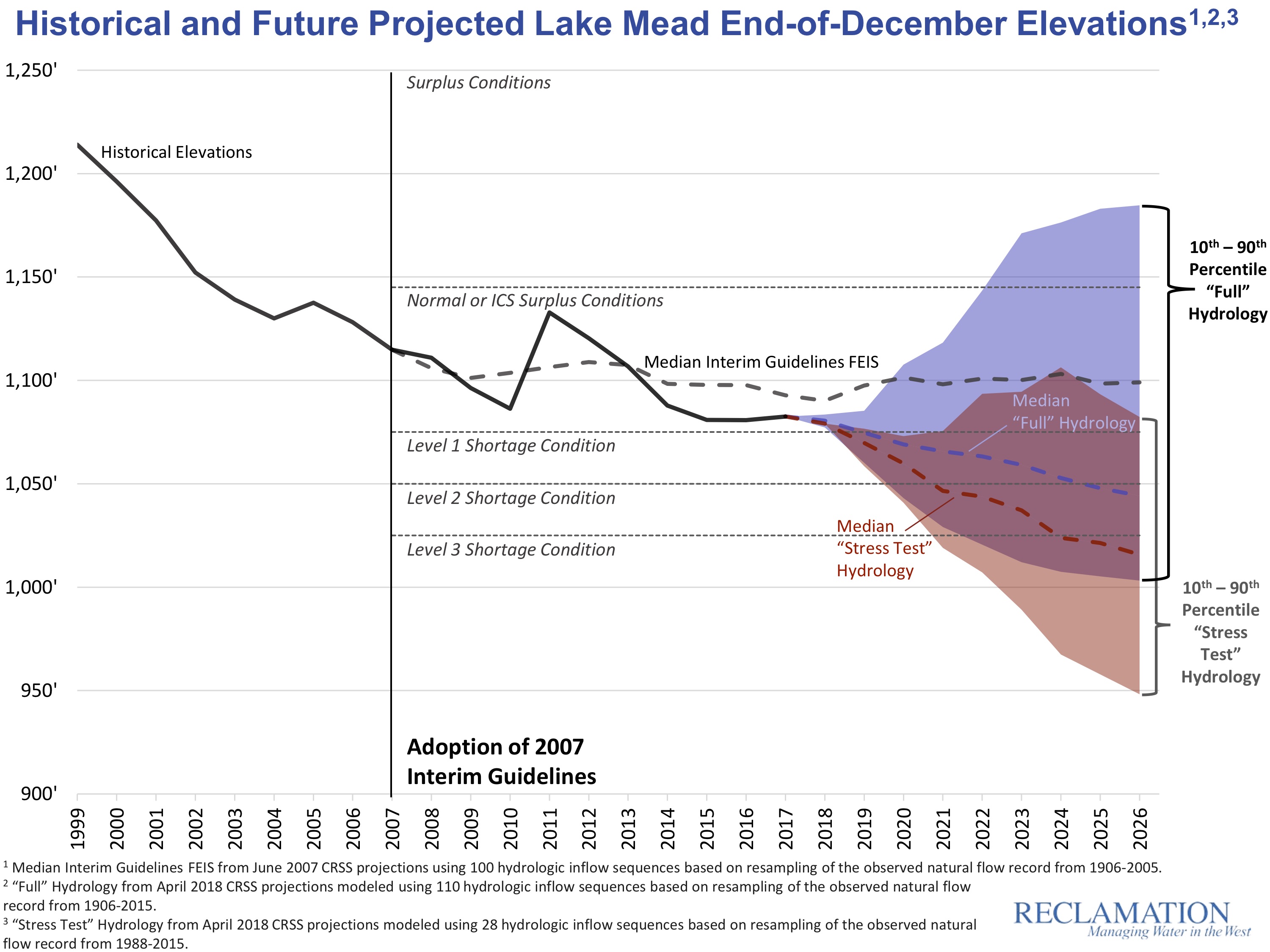

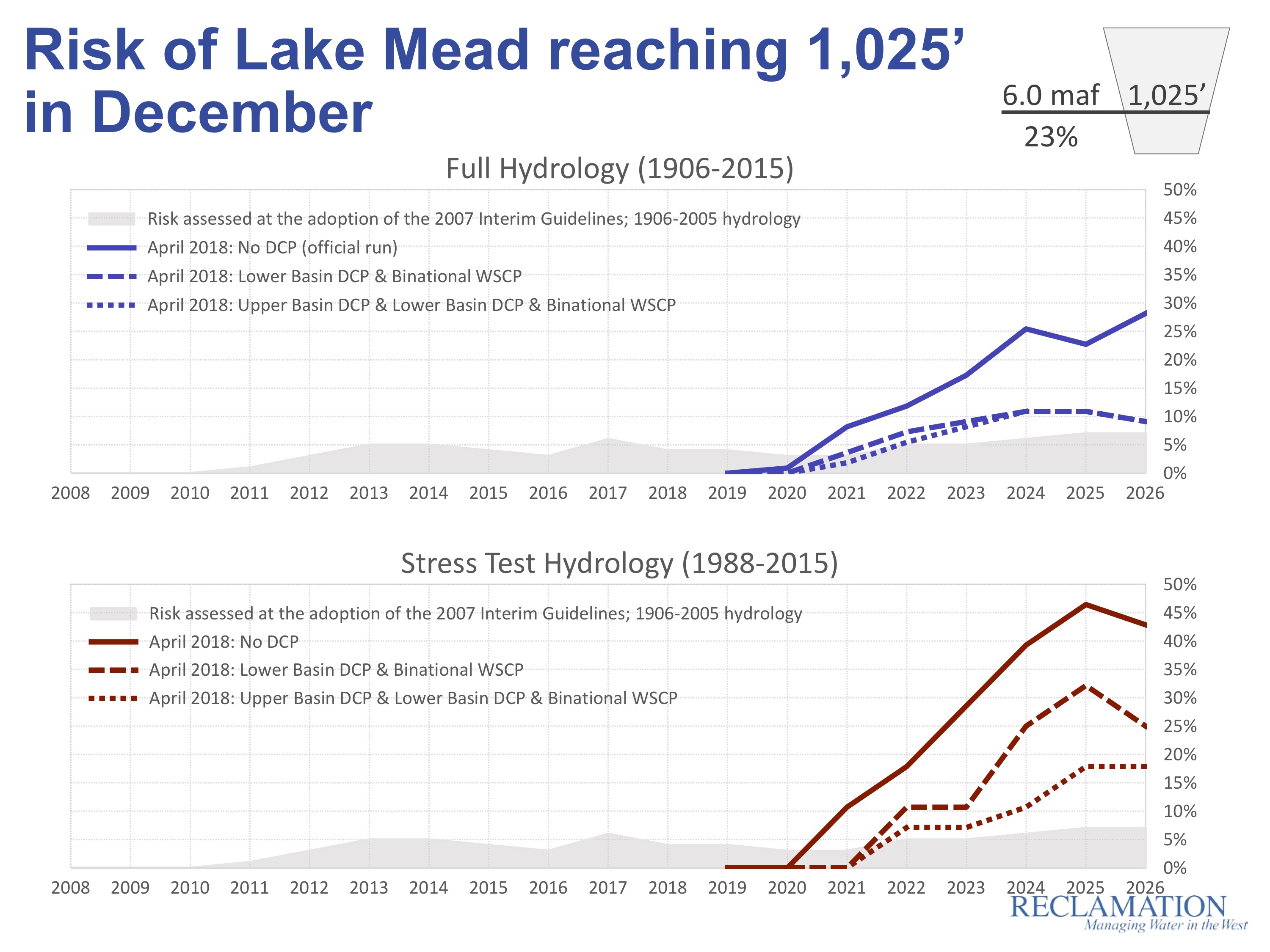

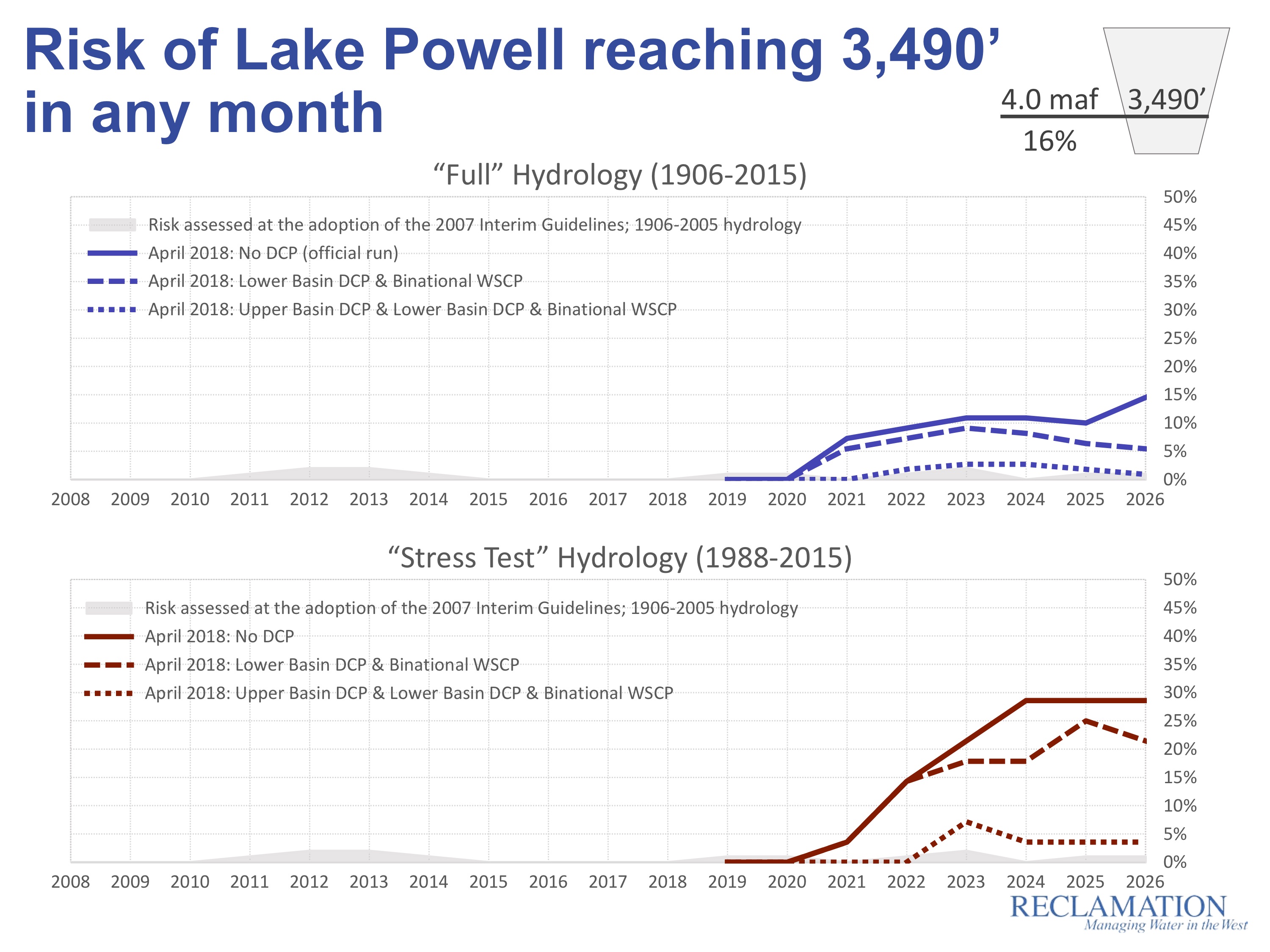

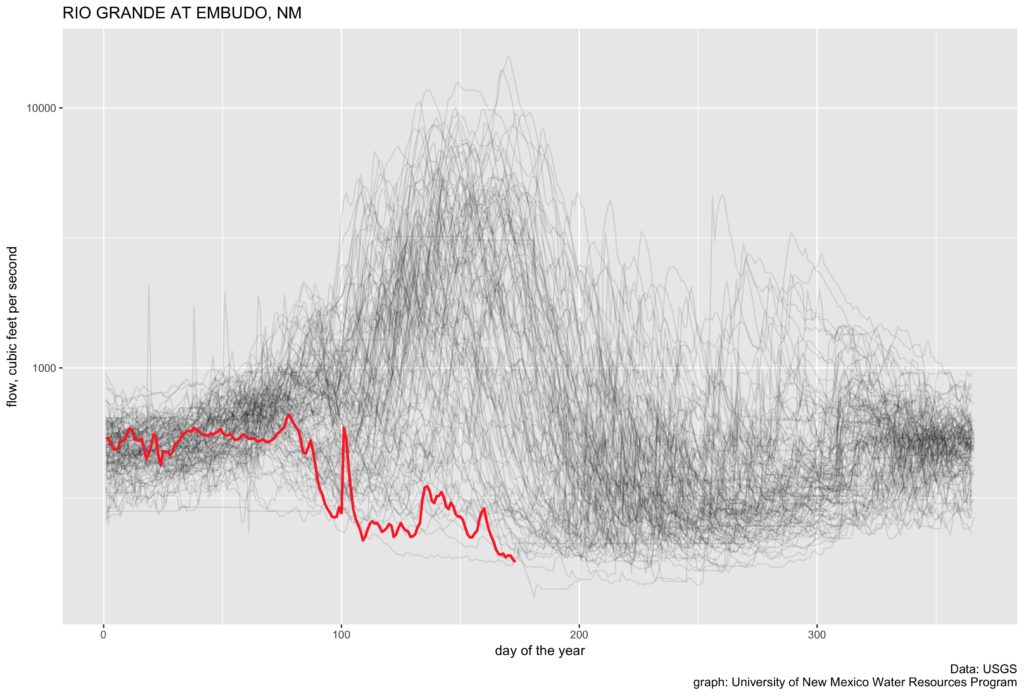

The problem the Upper Basin states – Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico – are trying to avoid is a “call” on their Colorado River Compact obligation to deliver 75 million acre feet of water past Lee Ferry every ten years (lawyer fine print alert: maybe it’s really 82.5 million acre feet every ten years if you include water for Mexico and whatever you do don’t call it an “obligation to deliver” because Upper Basin lawyers will wag their fingers and explain that it’s really an obligation not to deplete). If Lake Powell drops too low too fast, this could be a problem, so some sort of planned, staged conservation effort ahead of time might help forestall the risk. But without some way to earmark and account for the water, the Upper Basin states have been leery of expanding the effort.

Wyoming State Engineer Pat Tyrrell, who took the lead at this afternoon’s meeting explaining the decision, drew a distinction between “system water” and “state water”. What the Upper Basin states are looking for, he explained, is some way of tagging the water saved as it builds up in Lake Powell, so that if a Compact call were ever to come, it would be clear who had contributed what to meeting the Upper Basin’s obligations.

In the Lower Colorado River Basin, new rules negotiated in 2007 created a category of conserved water called “intentionally created surplus” (ICS) – big water agencies, especially the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, could conserve water and leave the savings in Lake Mead, earmarked with Met’s name on it in the Colorado River accounting system for future Met use. This was a big deal at the time, removing the conservation disincentive created by the problem that without such an accounting system, conserved water simply reverted to other users as “system water”.

The Upper Basin states would like something similar, and there was apparently some progress at this week’s meetings in Santa Fe on that front. Creating some sort of an ICS-like water bank in Lake Powell (or somewhere else in the Upper Basin reservoirs) would take approval of all seven states and, likely, formal authorization by Congress. There appears at this point to be general agreement on the concept among the Lower Basin states (Nevada, Arizona, California), but with a lot of details to work out. But it sounded like there was a green light coming out of the closed-door Santa Fe meetings of Basin States principals, which is an optimistic note in an otherwise somewhat tense time in Colorado River water management.

It’s important to remember the word “Pilot” in the program’s name. This effort, begun four years ago, was an experiment to understand how much it might cost, how to manage a pretty complex effort, how to account for the savings, and what the institutional structure around it would need to be to accomplish the goal of heading down this path to reduce Upper Basin water use. It’s that last point that is important. In coming to terms with the on-the-ground, practical difference between “system water” and “state water”, we’ve learned a great deal that is useful in figuring out where to go next with this stuff.

In the meantime, Upper Basin System Conservation is on the shelf.