By John Fleck, Eric Kuhn, and Jack Schmidt

As stakeholders negotiate the current crisis on the Colorado River, we believe the representatives of the states of the Upper Basin – our states – are making a dangerous argument.

Their premise is simple. With deep cutbacks needed, the Upper Basin states argue that their part of the watershed already routinely suffers water supply shortages in dry years. Without the luxury of large reservoir storage along the rim of the watershed that might store excess runoff in wet years and supplement supplies in dry years, the argument goes, the Upper Basin is limited by the actual mountain snowpack in any given year.

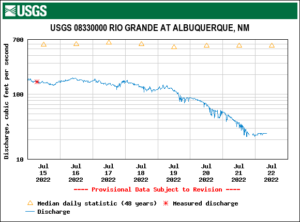

This is certainly true in many places. One of us (Fleck) lives in a community (Albuquerque, New Mexico) that has routinely seen supplies of trans-basin San Juan-Chama Project water shorted because of bad hydrology in a given year.

That is also the case for the oft-cited Dolores Water Conservancy District, which has junior water rights to the supply provided by McPhee Reservoir that is part of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Dolores Project. In contrast, the adjacent Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company has pre-Colorado River Compact water rights and its access to the same water source is relatively unlimited. The argument of the Upper Basin states about using less water in dry times applies in many local settings, especially in the local context of prior appropriation water rights. The argument is certainly logical.

But when one considers the regional scale of the entire Upper Basin, the argument is not supported by the data in the Bureau of Reclamation’s Consumptive Uses and Losses reports.

Our review of those data suggests that, on average, overall Upper Basin use is slightly greater in dry years, and less in wet years. While questions have long been raised about these data, they are the best that we have and, more importantly for this discussion, they are the data that the Upper Colorado River Commission has been using in support of its argument.

Here’s what the reports show for the 21st century concerning total Upper Basin consumptive Uses less net evaporation from the CRSP Initial Units (Lake Powell, Flaming Gorge, and the Aspinall Unit):

- in the five driest years ( 2002, 2012, 2013, 2018, 2020), the average was 4.06 MAF/year.

- In the five wettest years (2005, 2008, 2011, 2017, 2019), the average was 4.01 MAF/year.

- in the middle 11 years (the remainder), the average was 3.81 MAF/year.

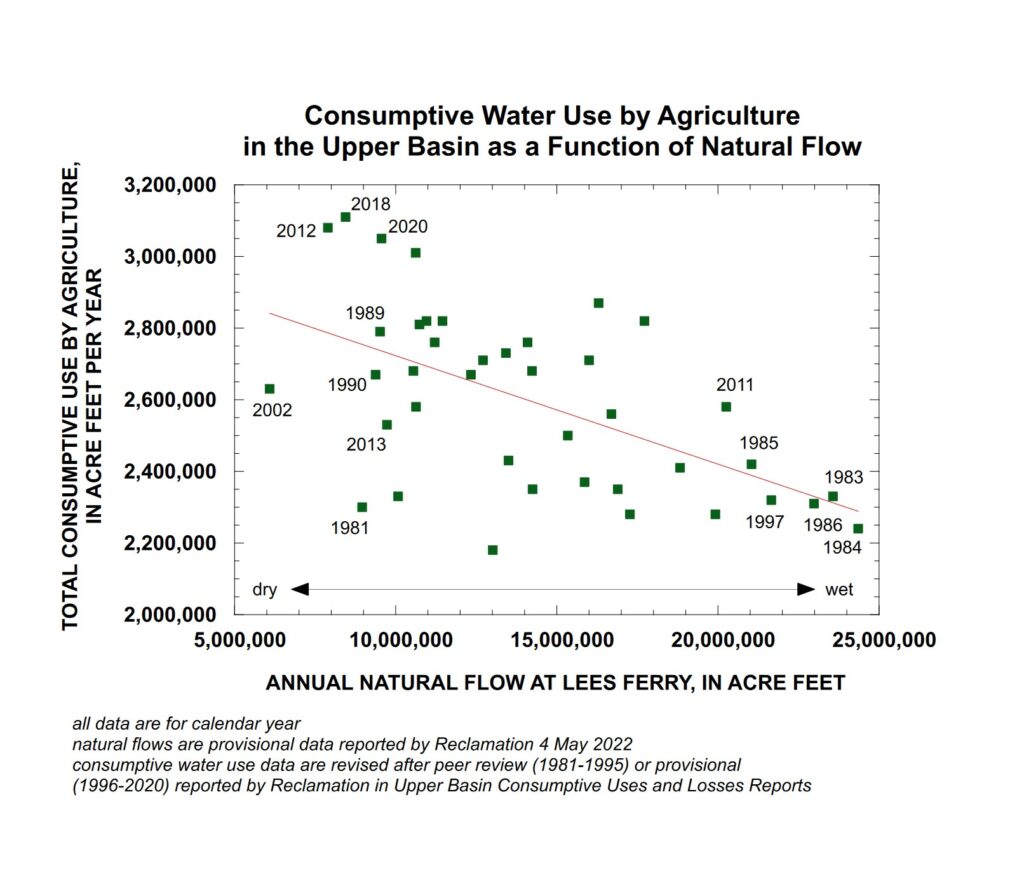

Upper Colorado River Basin agricultural water use in wetter and drier years. Graph by Jack Schmidt, Utah State University

Importantly, a scatter plot of Upper Basin agricultural water use since 1981 shows, in general, the opposite of what is being claimed. While agricultural use varies greatly from to year, in general, use has been greater in dry years and less in wet years.

In this plot, the estimated natural flow at Lees Ferry (a good representation of whether any individual year was wet or dry) is plotted against the summed agricultural use of water by all of the Upper Basin states. This simple analysis provides results counter to the assertion of the Upper Colorado River Commission in the sense that agricultural use of water was greater in years of low natural flow at Lees Ferry and was less in years of high natural flow at Lees Ferry. Thus, this simple relationship indicates that agriculture uses less water in wet years and more water in dry years, which is exactly the opposite of the assertion by the Upper Basin community.

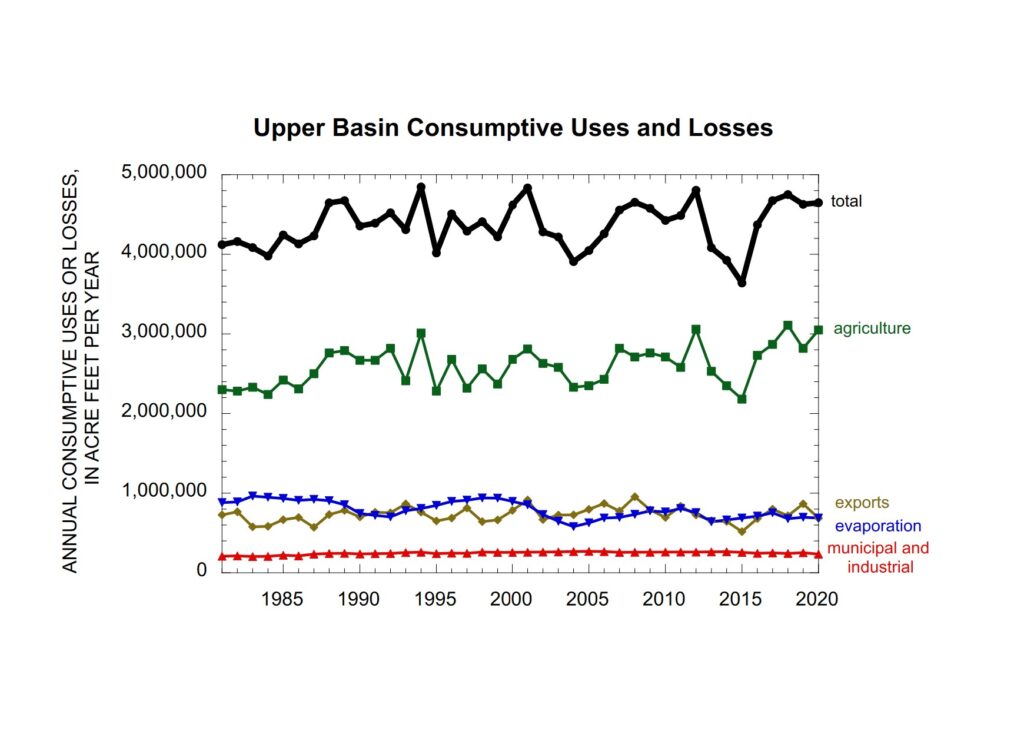

Upper Colorado River Basin water use over time. Graph by Jack Schmidt, Utah State University, based on USBR Consumptive Uses and Losses Reports

Another way of looking at this question is to consider the long term temporal trend. If the Upper Basin’s argument was correct, we would see a decline in agricultural water use in the 21st century, because the river’s flow shrank during the aridification of the 21st century. However, use has not decreased.

There are important nuances in the data. In the second year of some consecutive dry years like 2012-2013, the Upper Basin’s total consumptive use drops significantly, perhaps because local storage is depleted in the first year and doesn’t fully refill in the second year. This may be the situation in 2020-2021 as well.

Why do we view the argument as dangerous? Because Lower Basin interests can do the same math we have. They almost certainly already have. That leaves the Upper Basin with a fragile foundation for entering the negotiations over the compromises that are certain to be needed to modify the Colorado River’s allocation rules in the face of climate change.

Authors:

- John Fleck is Writer in Residence at the Utton Transboundary Resources Center, University of New Mexico School of Law

- Eric Kuhn is retired general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District based in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and spent 37 years on the Engineering Committee of the Upper Colorado River Commission

- Jack Schmidt is Professor of Watershed Sciences and director of the Future of the Colorado River Project at Utah State University