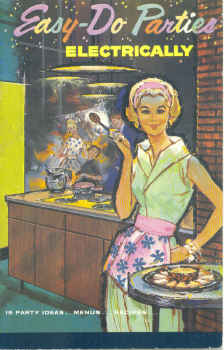

Easy-Do Parties, Electrically

I’ve always wanted it to be a “frequently asked question” here on Inkstain, but to be honest, no one’s ever expressed any curiosity whatsoever about the Easy-Do Parties Lady who has graced my blog lo these many years. But you should have asked, right?

She’s the cover gal on “Easy-Do Parties Electrically,” a 36-page recipe book from 1960 that I picked up for a quarter years ago at my neighbor Doris’s garage sale. It’s from the era of “live better electrically,” an ad campaign that (I think) was sponsored by General Electric. (Parties are a breeze with portable electric appliances.) She knows how to make “Strawberry Surprise” and “Apple Flip,” and, I mean, just look at her! You can tell she’s got her shit together.

I scanned her and slapped her on Inkstain years ago as an icon because I thought of the blog as a sort of electrical party spot, and she seemed the perfect hostess. I mean, she’s got her shit together.

After the first post-Party Lady Inkstain redesign, my sister Lisa complained that she was gone, so I restored her to her rightful place, and she’s stayed ever since. When I started doing social media, I used her as my first avatar as a lark. That stuck too, partly because I love the whole gender ambiguity thing (I also wear pink socks) so now she’s my “face” on Twitter and Facebook. (I once made someone’s “interesting science women on Twitter” list.)

I mean, look at her! Who wouldn’t want to come to her party? She’s got her shit together!