For today’s #tbt (Throwback Thursday), a return to the remarkable era of Steve Reynolds in New Mexico water management, and that time Reynolds tried to give New Mexico an effective veto over the Central Arizona Project.

Students in this year’s UNM Water Resources Program spring class are doing a case study this year on New Mexico’s bit of the Gila, a Colorado River tributary that begins with the meager snow that falls in the mountains of southwestern New Mexico. So I’ve been reading so I have smart and/or fun things to say during class. Mostly fun so far, the Gila’s complicated, I don’t feel smart yet.

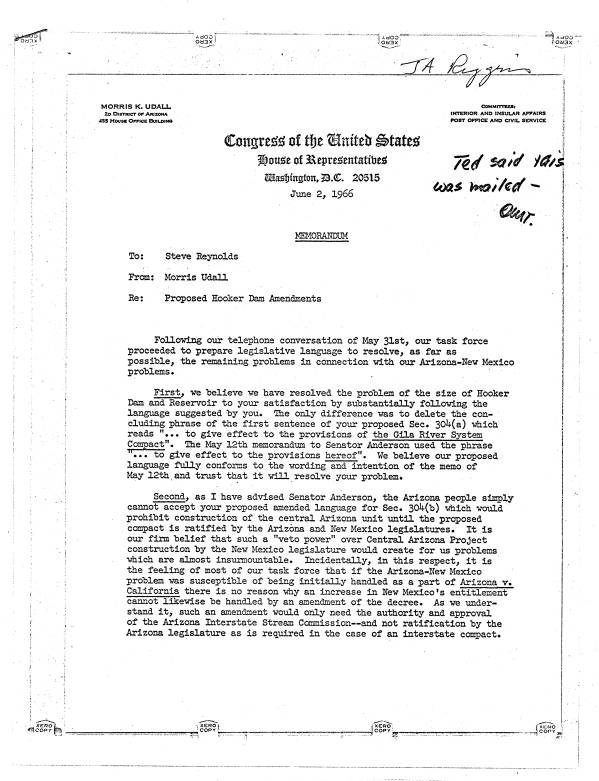

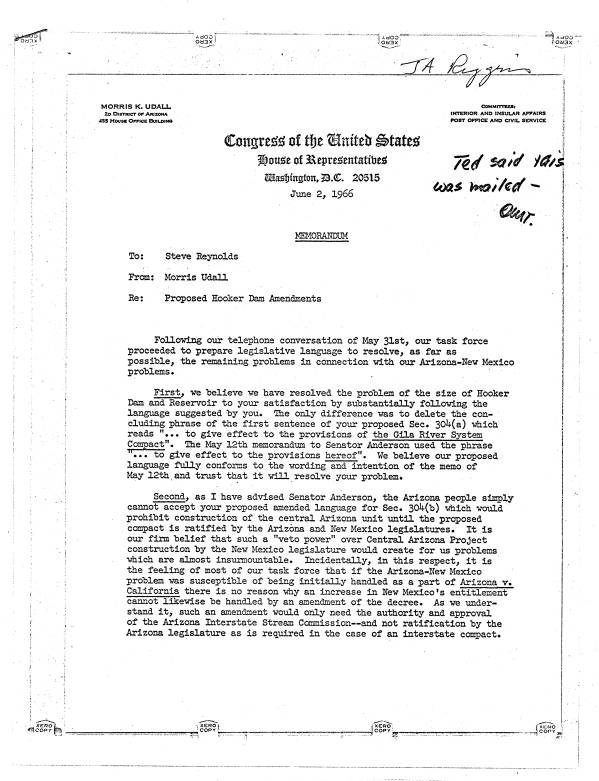

Back in the mid-1960s, Arizona was trying to win congressional support for the legislation needed to build the Central Arizona Project, its big straw to suck water out of the Colorado for Phoenix, Tucson, and parts there around. That took support from New Mexico’s congressional delegation, in particular the powerful Clinton P. Anderson. Anderson turned to our then state engineer, Steve Reynolds, to draw up the specifics of our ask. Reynolds said we needed Hooker Dam, a dam on the Gila as it flows out of New Mexico that had been on the reclamation community’s grand wish lists since at least 1946.

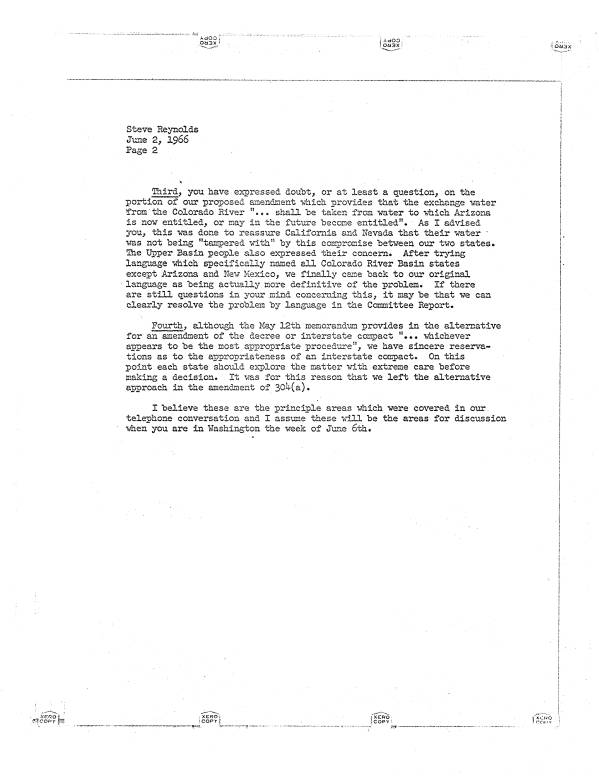

He also demanded (I toyed with “asked for” in this sentence, buy hey, it was Steve Reynolds, I’m guessing “demanded” more accurately captures the flavor of 1960s-era Steve Reynolds water governance) that the Central Arizona Project not be built until New Mexico and Arizona had negotiated a Gila River Compact.

Mo Udall, Arizona’s 2nd District congressman and one of the state’s leads in the negotiations, was happy to put the Hooker Dam language in the proposed legislation, but the demand for a compact was full stop. Any compact would require the approval of the New Mexico legislature, which was a balance of power pill too hard for Arizona to swallow. “It is our belief that such a ‘veto power’ over Central Arizona Project construction by the New Mexico legislature would create for us problems which are almost insurmountable.”

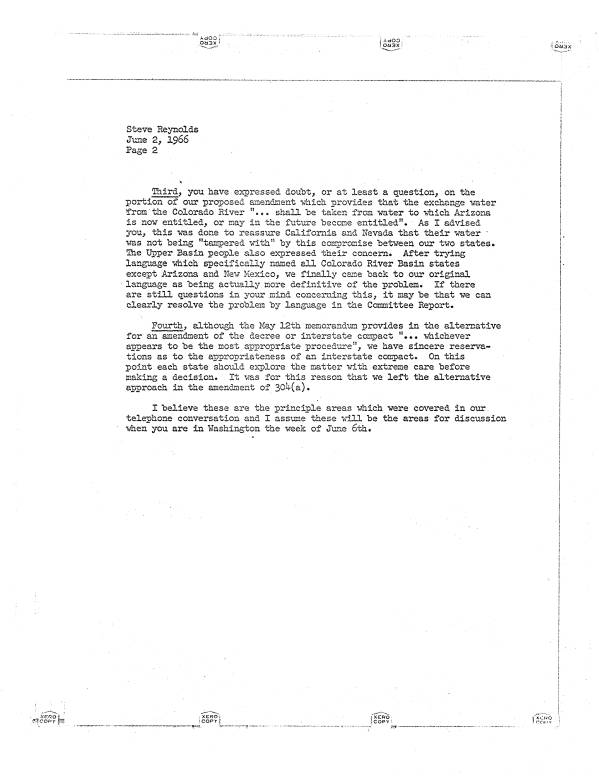

We didn’t get a compact. And they never built Hooker Dam.

Here, via the Western Waters Digital Library, is Udall’s letter:

Udall to Reynolds, 1966, p. 1

Udall to Reynolds, 1966, p. 2